Deconstructing the “F1 driver as gladiator” myth with Cars at Speed

Or: how to make sure your romantic nostalgia is at least painfully accurate

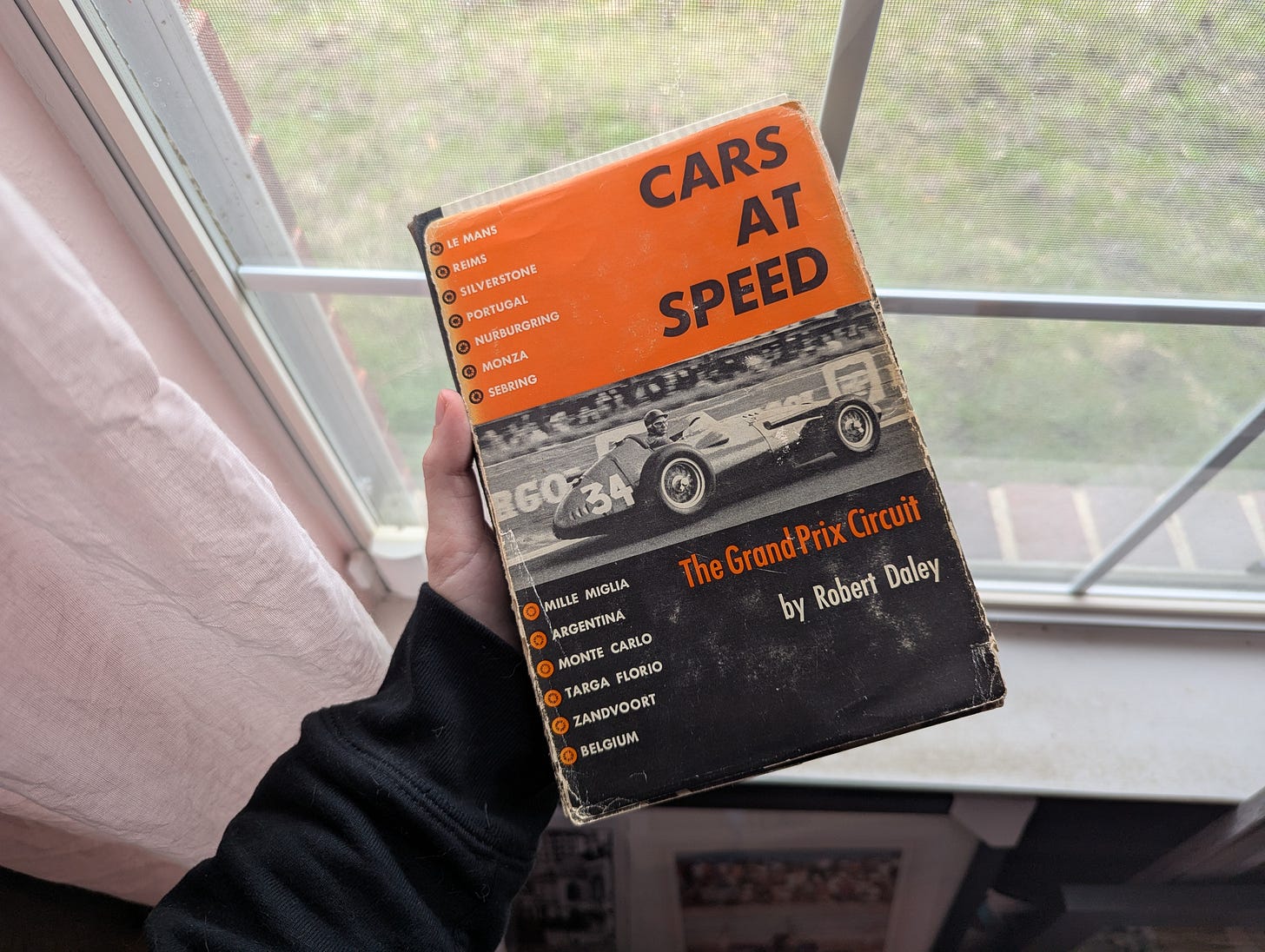

I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve read Cars at Speed: The Grand Prix Circuit by Robert Daley. Published in 1961, the book digs into the early history of some of the biggest Formula 1 and sports car races — Monaco and the German Grand Prix find space next to Le Mans and the Mille Miglia — in such a way that you learn both facts of the event as well as Daley's impressions of those drivers competing in the late 1950s and early 1960s. And it’s Daley's impressions that make the book what it is.

I read a lot of motorsport history. Some of it is better than others. Some authors never really seem to understand racing, so it leads to surface level observations, or an overall reliance on hard facts that strips away a lot of narrative possibilities — and motorsport fans looking for meaning will say, “Oh man, all these drivers kept racing even though their competitors were dying left and right! That must mean they're like gladiators!”

As a result, you'll see this sentiment argued as frequently by the fans who tuned into F1's so-called golden era live as well as by a lot of folks who are a generation or two removed.

The gladiator myth offers a framework, but unfortunately, not a very interesting one. It ends up stereotypical and reductive. You're left with a perception that all drivers from the past were tough and brave, that they were risking their lives for glory and fame, and that while their deaths might be a tragedy, they were ultimately noble tragedies.

It lifts the legitimate lived experience of these drivers out of the equation and replaces it with a limited set of motives and personalities to choose from. It ignores that the reality of the matter is far more complex and compelling, that there are as many negative characteristics about these drivers as positive ones. It revokes the agency of the drivers (as well as all the other people who make up the tapestry of the motorsport scene), and it replaces the uncertainty of possibility with a very definitive narrative about how history actually went.

What do I mean by that? Let's consider Alfonso de Portago, who plays a big role in the Mille Miglia chapter of Cars at Speed. Looking back from our contemporary timeframe, the depth of his life story has been flattened into “bold gentleman driver risks his life for glory, dies with honor.” It's a simple, easy-to-digest packaging that kinda makes you feel good about that death — because, y'know, Portago died doing what he loved.

Then you read Cars at Speed and learn about Portago from the perspective of someone who actually knew and met him, and who also knew and met his colleagues. Daley describes Portago as a real human being, with the assorted complications and unflattering behaviors that entails.

I want to pull a little section out here, because I think it's gorgeous:

Looking back, it is obvious that Don Alfonso Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton, seventeenth Marques de Portago, was a fool, that he was rushing toward violent death with a grin on his face and a cigarette dangling from the corner of his mouth. But at the time one tended to admire his fierce belief in man's right to play the game his own way, to envy the excitement he experienced to suppose that he — and he alone — could go on that way forever. Those older or wiser knew he couldn't, but some of them respected him for trying, and some loved his insouciance, his courage and flair.

“If I die tomorrow,” Portago remarked near the end, “nonetheless, I have had twenty-eight wonderful years.”

[...]

His fellow drivers considered him tenacious, daring. They were a little afraid of him, for he wanted to be world champion more than any of them, had less fear than they had, and did what he felt like doing at all times. He had burst upon their scene — in less than three seasons he was the best known personality in motor racing, though far from the best driver.

There is definitely a sense of romance in Daley's description, of course — but it's also tempered by real, actual details about Portago soon after:

Portago himself was courteous and articulate (in four languages) to journalists. He was also curiously gentle and modest. Tales of his hair-raising exploits came from others, not himself, and when confronted by them he appeared embarrassed and was reluctant to elaborate.

Weekend after weekend he risked his life. It was a compulsion which he tried to explain by asserting that during moments of peril, every nerve in his body seemed alive, alert to all the sounds, sights, and smells around him.

But speed was more than a search for excitement. “A man has to find something he can do well,” he insisted. “Not only well in itself, but well in relation to the way other men are doing it. I can drive that well.” He predicted he would win the driver's world championship by the time he was thirty. Then, before he was thirty-five, he would quit racing.

After that?

“I don't know,” he said restlessly. “There are many things.” Politics interested him. He told some intimates that with his name, background, and the world championship he could almost name his post in the Spanish government.

“The trouble with life,” he remarked, “is that it's too short. But I'm certainly not going to spend the rest of my life driving race cars.”

While you can still see Portago as a gladiatorial figure, Daley also wants you to understand that he was a fool. That he was kind. That he made mistakes. That he was naive. That yes, it was easy to get swept up in his seemingly heroic persona, but that beneath that façade, he was human just like the rest of us.

I'm a historian, but I also approach history with my creative writing lens firmly in place. Humans are messy and complicated; race car drivers are no different, and when I'm researching the life of a person I have never met and will never have the opportunity to meet, I have to rely on what writers of that era were saying. If they're just describing these men as one-dimensional, gladiatorial archetypes, then I don't actually learn anything about who they really were. I gain one interpretation of their existence, often filtered through secondhand information and the passing of time. Meet those drivers in the moment, though, and they're funny, kind, confused, and maybe even a bit willingly dumb.

Daley introduces us to so many different characters in this book — men who lived and raced and maybe died during the late 1950s, who had the same all-consuming passion to win races and could easily be painted with the same brush. Except, all of those men are painted with different strokes and different colors.

There's Jean Behra, who was so dazzled by the French love for racing drivers that he came to believe himself a national hero, with all of the nonexistent accolades and immortality that the title endowed. Daley describes him as falling victim to the belief in his own greatness, which resulted in a driver who was careless and often foolish behind the wheel.

There's Stirling Moss, whose no-nonsense dedication to racing was equalled only in his no-nonsense approach to the business of racing: We meet 30-year-old Moss while he's writing his fifth book on motorsport, jetting off to various BP fuel stations to make public appearances that net him tens of thousands of dollars, pushing himself to race around the world. A beloved figure in the British racing world, Moss seemed able to resist the temptations of greatness by simply putting his head down and getting on with things.

There's Phil Hill, a man whose philosophical musings on motorsport often leave him seeming like a little bit of a hopeless creature who knows he's in love with something that will never love him back. Daley loves pulling quotes from Hill, because Hill isn't afraid to point out a dangerous car, a stupid driver, or a track that needs treating with respect. He's shown telling autograph-hungry children that he's “nobody” before being wracked with guilt about doing so before ultimately justifying his decision by saying “they'd only throw them away tomorrow.” Behind the wheel, Hill is able to find peace; outside of the cockpit, he's haunted by what he does for a living.

I think the most particularly incredible thing is the fact that this book purports to center on the histories of the best racing circuits in the world — and it does that with rich, unflinching poeticism — but that the real stars of the book are the drivers that populate those circuits. Daley recognizes that motorsport's appeal comes as much from the power of a car as from the magnetic draw of the drivers who ignore good sense to muscle those machines around dangerous ribbons of asphalt. The result is a book that feels as alive today, six decades later, as it did when it was published.

My thoughts about Cars at Speed by itself are pretty much complete, but I do want to offer a more contemporary example of a “race by race breakdown” book: The Grand Prix Year: An Insider's Guide to Formula 1 Racing by Phillip Horton.

I love a good moment of synchronicity, and I've had this happen with both of my DPTJ book club reads so far: As I wrap up an older book, I start reading a modern publication that feels like an echo of what I've just finished. Cars at Speed focused on the history of key events, and those chapters were filled with both historical fact, narrative color, and conversations with drivers who were either from the country in question, or who had been involved in a key race at the venue being discussed.

Horton's book is somewhat similar, at least as far as the structure goes: He offers a brief history of each Grand Prix venue on the calendar and situates it with information about how that race functions organizationally. He, too, relies on local drivers to share their perspective of their home event.

The biggest difference is that I think Horton's book is more objective, while Daley's is more subjective. Part of what makes Cars at Speed such a romp — even in its darker sections — is the fact that Daley doesn't hesitate to convey his true thoughts. He opts for loaded language that would be discouraged in modern reporting, and as a result, he feels like the narrator. There are tons of facts, yes, but they're couched in the language of emotion and personal experience.

The narrative POV of Horton's book feels more objective, more journalist-y, more factual. His perspective will pop in via fun quips, but overall, he isn't saying anything that can't be backed up with a citation. That's not an indictment, more just an observation on the kind of writing that the motorsport space produces and values, and how it has evolved from 1961.

If you don't already have a copy of The Grand Prix Year in your hands, go get one ASAP.

I also enjoyed The Cruel Sport by Daily