DPTJ Script: Camille du Gast: France's extraordinary first woman racer

On racer, ballooner, fencer, skier, tobogganer, and animal rights activist Camille du Gast

Camille du Gast wasn't the first woman to get behind the wheel of a race car, but she was the first woman who gained international recognition for doing so when she began taking part in grand epreuves as early as 1901. She was the first woman in France to earn a driver's license, the first woman to hold an official role in the Automobile Club de France.

But to call Camille du Gast a racer and nothing else would be to diminish a lifetime of accomplishments. She donned the title of exploratrice, traveling the world while also competing in motor boat racing, fencing, skiing, tobogganing, fencing, and hot air ballooning. She was the controversial subject of a pornographic scandal, and the intended target of a failed murder plot hatched by none other than her only daughter. And while that might have been enough to push a person into hiding for the remainder of her life, Camille du Gast wouldn't be silenced. Instead, she became a prominent activist campaigning for the rights and dignified treatment of both women and animals.

This week on “Deadly Passions, Terrible Joys,” we're delving deeper into the remarkable life of Camille du Gast and situating her turn-of-the-century accomplishments within the greater context of women in motorsport.

Motorsport and the Belle Epoque

Those blessed enough to live in Paris, France at the end of the 19th century were able to experience an era known as the Belle Époque, which translates to English as “the beautiful era.” Nestled between the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and the onset of World War I in 1914, this was a period characterized by optimism, peace, innovation, and experimentation within certain regions of Europe.

Part of the reason this era is remembered so fondly among historians is thanks to the fact that the Belle Époque exists in stark contrast to the earlier years of the century, where the Napoleonic Wars and the Franco-Prussian War saw drawn-out, bloody battles wrack the continent as France attempted to exert its influence over all of Europe. It's hard to truly thrive as a nation when your resources are being poured into geopolitical conflicts, and when that period came to a close, it was with a sense of relief: The upper classes of Imperial France could breathe a sigh of relief and take advantage of the good life.

I say “upper classes” because there were still huge swathes of the French population living in poverty, which largely discounted them from being able to enjoy the luxury of visiting new landmarks like the Moulin Rouge, or reaping the plunder of French colonization.

And as has been the case with so many other times of prosperity and peace, the Belle Époque was an era of innovation. Around 1870, we began to see a second Industrial Revolution. Whole industries were transformed by the implementation of mechanized labor, which allowed for greater production and a surge in profits for the owners of these businesses. This is around the time we start to see annual fashion trends popping up: Machines allowed for the rapid creation of clothing items, which could be produced in greater numbers and sold at lower prices. That allowed for the formation of a robust fashion industry, where designers and clothing companies could constantly tweak their designs, where magazines and newspapers could report on these evolutions, and where a whole market could begin to convince French folk to toss their old threads for something far more fashionable.

Another prominent innovation of the time? The automobile.

It started with a desire to improve the horse carriage. These eras of prosperity are generally characterized by a greater amount of free time, since people — particularly those in the upper classes — no longer have to spend every waking moment of their day just trying to survive. They have the ability to look at their surroundings and take stock of what needs improvement.

Carriages were a big one. Whether you were an upper-class elite or a peasant in the country, there was a good chance you had some kind of wheeled buggy that you could hitch to your horse in order to travel — but it wasn't always the most comfortable form of transportation. Basic carriages were made of wood, while newer and more expensive models could be crafted from metal, but both provided a rough ride.

So, with time on their hands, some Belle Époque tinkerers looked at improving their carriages. They began to experiment with suspension, finding ways to improve the quality of the ride. They began to look at the materials they were using to find ones that were lighter, stronger, cheaper. They even had the time to solve one of the seemingly inflexible irritations of the carriage: That it could be one hell of a noisy affair. Before long, horse-drawn carriages were as beautiful and refined as they were functional.

And if you're already toying around with carriage design, you're probably going to keep thinking about the ways you can refine this product. Once you've crafted your ideal carriage, you can step back and ask yourself what else needs improving. And, my goodness, wouldn't it be nice if you didn't have to hitch this carriage up to a horse?

For those of us who have only lived in the era of the automobile, I think it can be extremely difficult to understand the sheer level of industry, infrastructure, and labor required to use horses as transportation. On your own property, you needed somewhere for your horses to live, and you needed to feed them and care for them and muck their stalls and keep them healthy. If you were wealthy, you probably had someone doing all that work for you — but that didn't mean your life was horse-free. Horses were required at every level of the supply chain, for every kind of industry, and that's not even considering all the land needed to breed and feed them. In 1900, it was estimated that there were somewhere between 3 and 3.5 million horses in America's cities. We're not talking about all of America, we're talking about cities.

I truly don't think we can fathom the amount of poop on the roads, or the number of people required to shovel and maintain that poop. By the 1890s, cities across the world had a whole workforce employed to scoop up horse dung, but it was still almost impossible to actually keep up with the demand. On dry days, the dung turned to dust and blew in peoples’ faces. On wet days, it turned into sludge covering the street. In Paris alone, there were 3,500 men and women trying in vain to keep the streets clean, and the costs of hiring and employing those poop scoopers tended to skyrocket during times of plague and pestilence, as doctors and scientists at the time firmly believed that even the smell of dung along could cause widespread illness.

It should come as no surprise, then, that thinkers and tinkerers started looking for a different way of approaching transportation. Trains and boats were powered by steam and coal, which may not have been a wholly clean option but was at least far less smelly than the equine travel counterparts. There had to be some new way to make carriages move of their own accord — something that didn't require heaping piles of excrement.

In Germany, Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach invented a small combustion engine that they first outfitted to a two-wheeled machine similar to a bicycle in 1885. Not long after, they'd stuck that engine onto a coach and a boat to prove the versatility of their invention. Karl Benz was doing the same around the same time, receiving the first patent for a motorcar in 1886.

These self-propelled machines caught the attention of, well, just about anyone with an inventive bent, and manufacturing firms like Peugeot — which built everything from bicycles to crinoline dresses to steel saws — were quick to try their own hand at constructing their own take on these cars. Meanwhile, other firms were thinking of manufacturing smaller, single-person vehicles, which gave rise to scooters and mopeds, as Michelin started to manufacture the pneumatic tire.

Newspapers and magazines revelled in these new inventions, and as a result, one of the easiest ways to garner publicity for your automobiles was to compete in an early racing event. As we've touched on in previous episodes of “Deadly Passions, Terrible Joys,” these events were often organized by newspapers, with the whole goal being to traverse from one city to another as quickly as possible. Those early cars weren't particularly quick, or comfortable, or reliable, but they began to illustrate the possibility of a different future for transportation.

It wouldn't be until World War I that automobiles were really given their due. In times of peace, the vehicle seemed like a frivolity, and it was hard to imagine a life that wasn't so intricately tied to horses — but during the war, they became a necessity. More than 8 million horses, donkeys, and mules were killed during the Great War, and those that survived were observed to suffer from shell shock, or what today we'd call post-traumatic stress disorder. On top of that, feeding a small army of animals on top of your humans meant resources were almost always divided, and the slower pace of your four-legged transportation convoys meant they became easy targets for bombs and gunfire. Plus, you'd need to recruit vets and caretakers to manage these animals, along with your soldiers. Automobiles were nimbler, more agile, and required far less maintenance. There was also less of a likelihood that soldiers would develop emotional bonds with machines compared to animals.

But that's a story for another DPTJ episode; today, I want to keep us firmly in that Belle Époque, within the magic of the early automobile, because this brings us to one of my favorite things about these early periods of innovation: a lot of these new inventions didn't have associated rules or cultural norms just yet.

When we consider the automobile, for example, there was no early consensus on how these cars should be powered. There wasn't much creativity in the design yet — cars still largely looked like horse carriages — but there was no one to say how those cars should achieve propulsion. Combustion engines existed, yes, but so did steam engined-vehicles powered by coal, and electric vehicles.

It also meant there were no formal rules on the kind of people who were allowed or encouraged to drive cars (other than the wealthy, obviously). Motoring would go on to become associated with men, but in these earliest years, a wealthy, audacious woman was just as expected behind the wheel as her male counterpart. And womens’ early experiences with the automobile are exactly what we're going to talk about next.

Womens’ early experiences with the automobile

Today, automotive culture largely centers around the male experience. We think of cars as a masculine endeavor, with racing in particular still causing us to ask if we'll ever see a successful woman in a sport like Formula 1. But back when cars were first introduced to the world, many of those modern cultural assumptions hadn't been forged yet.

Jessica A. Brockmole, author of Pink Cars and Pocketbooks: How American Women Bought Their Way Into the Driver's Seat, argues that the evolving ideas of women and the new spheres they were beginning to occupy meant they weren't excluded from early automotive marketing. Newspapers and magazines advertised to both women and men, and when women were shown, she was shown in the vein of the Gibson Girl, or the New Woman.

The Gibson Girl started life as an artistic representation of the feminine ideal of the late 19th century, though it came to evolve into a kind of lifestyle. Gibson Girls were still quite thin and frail, though there was a new emphasis on their buxomness — albeit, without being vulgar. Most notably, though, a Gibson Girl was intelligent, perhaps even going to college in hopes of having a career, and she was also fit. This was the woman who had firmly adopted the bicycle as a means of both transportation and of physical exercise, who could stand on her own two feet… but who was ultimately expected to defer to a husband while still in her prime.

The New Woman was similar: Affluent but sensitive women who were independent and who could exert a certain amount of control over her own life. The New Woman archetype helped forge the suffragette movement that garnered women the right to vote, and she was often portrayed as riding a bicycle — a relatively affordable invention that allowed women to gain greater access to a public sphere that had largely been dominated by men. The automobile, then, was just a self-propelled extension of the freedom afforded by the bicycle.

Also of benefit was the fact that the earliest drivers and racers were usually pretty wealthy, so the ability to drive a car was coded more according to class than to gender. Camille du Gast, the subject of today's episode, was one such woman: She had enough money to effectively buy her legitimacy as a motorist. It was still a little bit of a surprise to see a woman driver, but when you considered the wealth necessary to buy early automobiles. In America, you could expect to buy a new car for around $1,000 in an era where your annual salary was probably somewhere around $500 a year.

If you were spending that kind of cash, well — it was highly unlikely anyone was going to discourage you from doing so just because you were wearing a skirt.

That being said, there were plenty of factors that made it challenging for women to easily integrate into the automotive world. First and foremost was the fashion of the era, which was characterized by voluminous skirts, puffy sleeves, tight waists, and veiled hats, all of which were at risk of being soiled — or of simply not fitting — in the early open-air motorcars of the early 1900s. If you've ever seen a bride in a ballroom gown try to squish into a car after her wedding, you'll get a sense of the chaos that comes along with lugging around several pounds of skirts and clothing.

There was also the fact that those early automobiles, particularly combustion-engined vehicles, were extremely physical to drive. Early gas-powered cars needed to be cranked by hand to start, and you needed to really put some elbow grease into it to make sure you could get the engine running on its own. It sounds simple, but it was strenuous work, and there was always a danger that the crank could kick back and harm the person cranking it. You'd often have to pull a throttle lever at the right time to fire it up, and if you got all that right, you'd be set to hit the road.

But again, that was only the start, because those early cars were often controlled by tillers. This was basically just a stick or a handle that you used to steer, and in this era before comfortable suspension or power steering, you needed to really ensure you had a grip on that bad boy because any wayward pothole or rut in the road could jerk the tiller out of your grip. Early steering wheels suffered similar problems, though there were at least some benefits to having both hands on a wheel for leverage. Plus, if you've been following “Deadly Passions, Terrible Joys” for a while, you also know that things like grease and water would need to be pumped by hand to ensure you didn't blow a motor.

Electric cars did exist at this time, but that technology stagnated in large part because electric cars were so strongly associated with female drivers — a mindset that had become deeply entwined with the automotive world as early as 1900. In a 1907 edition of a magazine titled Motor, writer Carl H. Claudy wrote, “Has there ever been an invention of more solid comfort to the feminine half of humanity than the electric carriage? What a delight it is to have a machine which she can run herself with no loss of dignity, for making calls, for shopping, for a pleasurable right, for paying back some small social debt.”

The small battery life meant that the spheres of travel were limited when you were driving electric cars, which was thought to be perfectly fitting for a woman, but inappropriate for a man who should have no limits placed upon his freedoms. Those ealy EVs were also cleaner and quieter — again, qualities associated with women. But anyone who took motoring seriously would be driving a combustion engine, with all of its associated noise and grime.

But there was still a wonderful exhilaration for women who got behind the wheel. In 1906, writer Edith Wharton, her husband, and her brother engaged in a road trip across France, where she wrote, “The motor-car has restored the romance of travel. Freeing us from all the compulsions and contacts of the railway, the bondage to fixed hours and the beaten track, the approach to each town through the area of ugliness and desolation created by the railway itself, it has given us back the wonder, the adventure, and the novelty which enlivened the way of our posting grand-parents. Above all these recovered pleasures must be ranked the delight of taking a town unawares, stealing on it by back ways and unchronicled paths, and surprising it in some intimate aspect of past time, some silhouette hidden for half a century or more by the ugly mask of railway embankments and the iron bulk of a huge station.”

Yet again, the automobile's association with World War I further created divides in the perceptions of motorists. Because those early cars found use as ambulances or personnel carriers, they became strongly associated with both combustion, because fuel was easier to come by than any battery-charging stations, as well as grime. These cars were machines capable of trundling emotionlessly through a battlefield, of withstanding gunfire and bombs and all manner of chaos being thrown at it. Nevermind the fact that women were recruited in droves to drive these ambulances through the battlefield, and that many of the most impressive female racers in the pre-World War II era had learned to drive in the midst of the war. The association of cars was with war; war was masculine; therefore, cars were for men.

But for that brief, fruitful period of the Belle Époque, where women were still the subjects of active automotive marketing, a group of truly phenomenal female racing stars began to emerge.

Camille du Gast: An early life

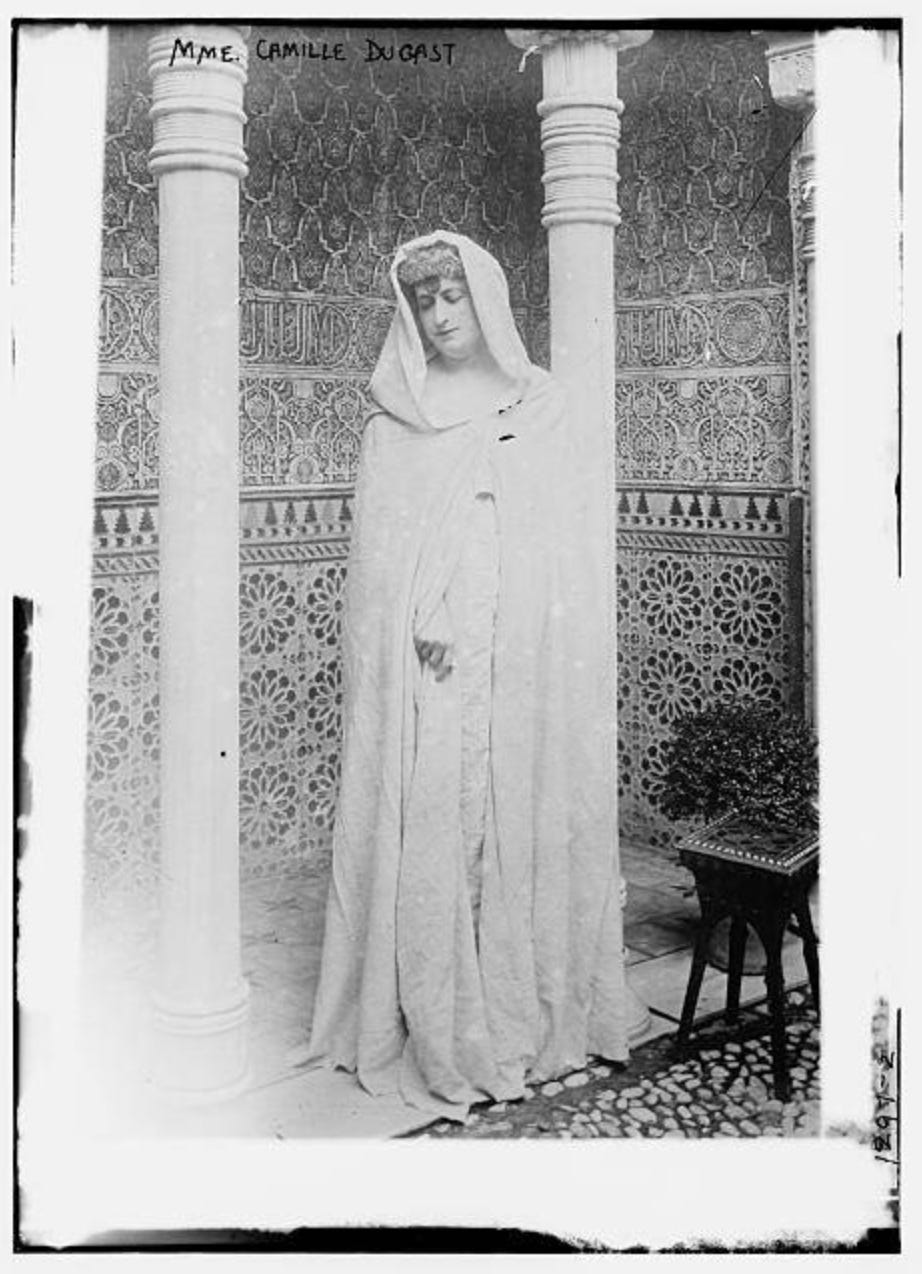

Her full name was Marie Marthe Camille Designe du Gast, and she was the youngest of her three siblings, born on May 30, 1868. Green-eyed, fair haired, and hailing from a wealthy family that could offer her the world on a platter, du Gast grew up with the distinct notion that she could do anything. By all accounts, her earliest years saw her adopt the guise of the garçon manqué — the tomboy.

We know very little about her early life, other than that her family was wealthy and that she was likely well-educated and encouraged to explore a slightly more liberal upbringing than one would expect from a young woman of that era. She was adventurous as a girl and likely took advantage of the stronger societal encouragement for young girls to take part in sports and other forms of physical activity.

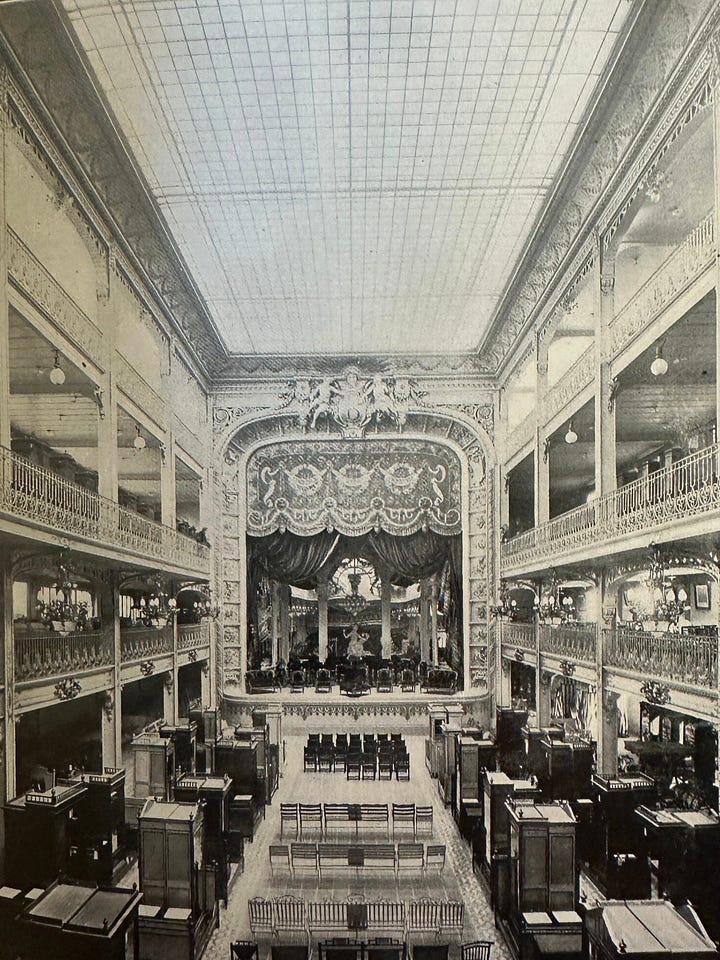

The record of her life truly begins in 1890, when at just 22 years old she married Jules Crespin. Crespin was majority stockholder and manager of Dufayel, one of the largest department stores in France that had been founded by his father; interestingly, the gorgeous and opulent building housed stores that catered more to the working class than to the wealthy, which made it the subject of some strong derision from the upper classes, but which provided a much-needed “third place” for plenty of people who had nowhere else to spend their leisure time.

Part of what made the place so popular was the fact that it used something called “credit notes,” which could be redeemed at hundreds of shops around Paris. By 1902, the shop was pulling in over $26 million per year. But it was also important because it became a sort of do-all venue, where residents could check out a free film, browse invention showcases to see the latest discoveries of the Belle Époque, see a concert, or simply just bring their own food for a picnic.

That Camille du Gast married into the family that founded this incredible shopping mall only allowed her to further her adventurous side, though her husband — who was himself infatuated by hot air ballooning — had just one request: She should compete under her maiden name. While he supported her various exploits in fencing, tobogganing, shooting, parachuting, racing, and more, he didn't want those exploits to be confused as some kind of publicity stunts for Dufayel.

And those stunts were impressive. Both du Gast and her husband were big hot air balloon fans, to the extent that they took advantage of a friendship with pilot Louis Capazza to be shuttled to parties and events. In 1985, du Gast naturally took her love of this new sport to the extreme, organizing a parachute jump from a hot air balloon hovering over Paris at about 2.000 feet. Allegedly, she was the first woman to use a parachute, and she's also said to have set a distance record in the process regardless of gender, but I will say that it's hard to find evidence to either prove or disprove those records. I am, however, quite confident that she was the kind of woman to jump out of that balloon just to see what it was like.

Exact dates here are a little challenging to come by here, so I'm going to report both stories. One story says that it was Jules Crespin who, in 1901, purchased the Peugeot and Panhard-Levassor automobiles that kicked off du Gast's infatuation with the racing world. Another states that Crespin died young, somewhere between 1896 or 1897, when Camille du Gast was just 27 years old. The fact of his early death is certain, because du Gast was a widow with a young daughter named Diane and a hefty inheritance by the time she got behind the wheel of a race car.

After just six years of marriage, du Gast was left to find a new path forward, which she did by throwing herself into any form of competition she could find.

Though she likely would have gained some experience behind the wheel while her husband was alive, she didn't officially earn her license until 1898, after which time he'd died. Plenty of people believe that she’s the first woman to do so, while others allege that Anne de Rochechouart de Mortemart, Duchess of Uzès, was pursuing a license right around the exact same time.

Driving itself was likely a thrill, but it wasn't long before she learned that this skill could be made even more thrilling. On June 14, 1900, Camille du Gast was one of countless spectators who had flocked to Ville-d’Avray, a suburb on the outskirts of Paris, to watch a handful of racers launch off the start line for the Gordon Bennett Cup which traversed a 353-mile route from Paris to Lyon. The Gordon Bennett Cup wasn't the first race in history, but it was the first one to make a point of pitting international drivers and machinery against one another with the express purpose of offering a prize at the end.

It's worth a brief deviation to talk a little more about Mr. James Gordon Bennett Jr., because he would indeed play a role in Camille du Gast's life — with some rumors alleging that the two were even lovers.

Bennett was born in New York City in 1841, inheriting the New York Herald publishing empire from his father. With plenty of money to his name and a keen interest in sport, he's credited with hosting the first polo match and the first tennis match in the United States, and he also won the first trans-oceanic yacht race in history.

An interest in yachts naturally lent itself to an interest in automobiles, and Bennett was well situated to witness the rapid growth of that technology in Europe as he'd moved to Paris in 1887. He saw the various ways these early vehicles were evolving all around Europe, and, ever the audacious sportsman, he wanted to be the man to inject a little organized competition into a rapidly growing field. City-to-city racing did already exist, but largely for exhibition purposes. Those early events were often sponsored by newspapers who intended to document the event to sell papers, but it was Bennett who added in a layer of national pride, as well as competition for the sake of a prize at the end and the accolades that came with winning a race with a very important name — such as, for example, the Gordon Bennett Cup.

Was it this added layer of competition for its own sake that appealed to the experience-hungry Camille du Gast? Or did her decision to start actively competing stem from her friendship with Bennett, who would have almost inevitably encouraged her to race her own cars?

Just over a year later, on June 27, 1901, Camille du Gast launched from the line of her first motor race, the Paris-Berlin Trail, behind the wheel of her 20-horsepower Panhard-Levassor that was designed for sedate cruises, not high-speed competition.

The race distance totalled 686 miles, though that total distance was divided into three different stages over three days. Some 110 vehicles took the start, but only 30-odd cars made it to the finish. Du Gast was one such finisher, allegedly finishing 33rd overall.

This is a little deviation, but I want to quote from the Scientific American here, a publication that covered the event as it transpired in 1901. It offers a really fascinating perspective on how motorsport was perceived at the time. It reads:

It may well be asked if the limit of speed in racing vehicles has been reached. It is not likely that it has, but the safe limit has been attained, and the higher the speed the more liable are the tires to destruction through excessive side strains in taking corners, in addition to the liability of puncture. Speed does not, therefore, depend entirely upon the motors; the tire is a factor of equal importance. It is almost impossible for even a trained chauffeur to carry on such sustained high speeds for days without physical collapse, the nervous strain being intense. Many of the French drivers in the recent race are still suffering from the results of the sport. The race, however, is intended to further the automobile movement all over the world by creating a great interest in it among the public, so that even though the technical lessons of the recent contest may not be very great, the net result must be gratifying.

Those of us looking back on this race in 2025 are likely thinking, well, duh — of course tires are important! They're the only part of the car that actually connects to the road, so the power of your engine doesn't really matter unless your tires can handle that power! But this is how early we were in the development of the automobile, and in our understanding of motorsport, which is to say: We understand very, very little.

We don't know how Camille du Gast felt about the race or her performance within it, but we do know that she didn't contest any additional races until 1903 — at least, not any recorded ones. I've found some sources that claim she may have entered the 1902 Paris-Vienna race, as well as that year's New York-San Francisco trial in America, but her name doesn't appear on the entry lists. It's possible she entered the events but wasn't accepted.

Without any racing record to follow, it's tough to know exactly what she got up to; some sources mention she went on an “extended cruise,” though they don't mention where she went. However, we do know that she spent a strong part of the year in court clearing her name from its association with a vaguely pornographic scandal.

The drama centered around a photo from 1885 titled “La Femme au Masque.” This image depicted the body of a woman who was completely naked, aside from a domino mask covering her face and a piece of cloth loosely hanging from her fingers, in front of her thigh. The identity of the woman in the photo wasn't publicly disclosed in 1902, and somehow, it transpired that members of du Gast's family accused her of being the model in question.

Du Gast sounds to have already been involved in some court proceedings with her father and her brother when their lawyer, Maître Barboux, brought copies of La Femme au Masque into the courtroom, to be distributed among the people there. He stated that he understood Camille du Gast was the model in question, and the accusation was salacious enough to send the rumor mill into a tizzy.

Du Gast claimed that, in fact, she wasn't the model in question, and she sued Barboux to clear her name. In her defense testified the original photographer, Henri Gervex, as well as the model in the image, a woman named Marie Renard.

Despite having the photo's two key participants speaking on her behalf, the court alleged that Du Gast didn't really have a case here, and the whole affair was dismissed. According to a newspaper report on the whole affair from Australia, it was “forbidden to report libel or defamation proceedings,” so the case had to be “taken in a general way.”

But we weren't done. Oh, no. When Barboux strutted from the court, he found two men waiting for him — one, a Monsieur de Marcilly, alongside the Prince de Sagan, who was one of Du Gast's many suitors. It was the Prince who accused Barboux of being an insulter of women, and he doubled down on his claim by either punching or slapping Barboux — again, the reporting differs here.

This was an offense worthy of a court case, and the Prince was fined 500 francs despite nevertheless claiming he “acted in good faith.” The whole affair eventually slipped from the papers without much of a satisfying conclusion for du Gast, aside from, perhaps, a more public recognition that she wasn't the woman in the photo.

Thankfully, there were greater goals on the horizon: Camille du Gast had entered the 1903 Paris-Madrid race behind the wheel of a 30-horsepower De Dietrich.

Scheduled for May, the Paris-Madrid event had been touch-and-go for months. The French government had grown hesitant about allowing races to take place on public roads, and after the 1901 Paris-Berlin event, France stated that no other races would be authorized. Baron de Zuylen, who was president of the Automobile Club de France at the time, argued that the roads were public, and that many local towns were actually quite interested in the idea of a race passing through their area. On top of all that came pressure from French automakers: How were they meant to sell and promote their cars if they never had a chance to exhibit them on the road?

The ACF had started taking applications on January 15, but it wasn't until the 17th of February that the French government finally gave its seal of approval to the whole affair. Over the span of 10 days, over one million drivers applied for the race, paying anywhere from 50 to 400 francs to be allowed a shot at entering. When the cars gathered in the early morning hours of Sunday, May 24 to depart from the Versailles Gardens, 224 machines actually appeared. While that wasn't quite one million participants, it was a frankly astonishing number of competitors, and hype for the event had been building for weeks.

Naturally, Camille du Gast was determined to participate, and the presence of a woman on this 812-mile route meant she was a media darling.

Ahead of the race, du Gast spoke to an American racing correspondent, saying, “I am already in training for the Paris-Madrid race. One has to get ready for an automobile race just as a jockey does for a horse race. There is not much time, for the start will take place on May 24. I shall have to be out early for my turn comes at four o’clock in the morning.

“I look forward with intense pleasure to crossing the Pyrenees and hope to experience the thrill of my life. My machine will be one of one hundred horse power. All the automobile nations of any note will be represented. There will be about 230 competitors. I am the only woman entered so far. Many of the machines are lighter than those used last year. If I win, or even if I make the distance in good time, which I am sure to do barring accidents, I shall go at once to America.

“The great automobile race of the future will be held in America. It is only there that the distances are sufficiently great. I shall challenge Vanderbilt or Winton or any of your great racers. I am surprised that no American woman has yet made a record at automobile racing. American women usually lead in everything. Perhaps I shall be the occasion of getting them to develop their talents in this direction.”

Camille du Gast had reason to be hopeful, but there's one part of her quote that would come back to haunt her. She stated she'd go to America ‘barring accidents.’

Unfortunately, accidents were the one thing the 1903 Paris-Madrid race had in spades, to the extent that it threatened the very existence of automobile racing.

Where to begin in listing the fatal flaws that plagued this race? First and foremost was the fact that, while there was plenty of interest in the build-up to the event, no one seemed to have any idea how much policing would be necessary on race day. Even though soldiers were brought in to keep spectators off the road, they were so dramatically outnumbered that it was a losing battle. An estimated 100,000 people flocked to the start, with over three million staged along the entire route.

Spectators continued to be a problem, even as the cars got further away from Versailles. But it was there that another concern rose: Dust. Rain had been nowhere to be seen in the two previous weeks, and officials had only bothered to water down the first kilometer of track. Competitors were launched from the start at one-minute intervals, which meant there was no time for the dust to settle in between runs. Drivers could hardly see, and to make matters even worse, spectators started crowding into the middle of the road to get a better view of the cars rocketing toward them.

The first starter of the day was an Englishman named Charles Jarrott. In the first leg of the race, they made a good start but broke down twice. They were by no means driving the fastest car, yet they noticed something perplexing: Only two cars passed them. Jarrott made it to the first checkpoint to learn he was still in the top three, then arrived in Bordeaux to complete the first leg of the race in second place. Time passed. A handful of cars trickled in, but not many. One man, Fernand Gabriel, passed 79 cars to arrive in Bordeaux. He reported that there were wrecked cars littered on the road.

I'm going to pull a section from Cars at Speed by Robert Daley here, because it very succinctly illustrates what happened that tragic day:

As more cars came in, each driver had horrors to report. Lorraine Barrow, driving a De Dietrich, had swerved to avoid a dog and crashed into a tree. He and his mechanic had been killed. He must have been doing eighty. Leslie Porter, driving a Wolsely, rocketed around a corner only to find a railroad crossing with the gates down. Jamming on the brakes he had skidded into a house. His mechanic was dead. Tourand, trying to avoid a child on the road, had skidded into the crowd, killing the child and some spectators, perhaps half a dozen in all, no one was sure. Delaney wrecked his car on a heap of stones. Gras crashed into a railroad crossing. Mayhew rammed a tree. Stead's car brushed against Salleron's, then careened off the road and crashed, killing Stead. Marcel Renault, closing up on another car, approached a long curve at nearly eighty miles an hour. The other driver refused to slow down. So did Marcel. In blinding dust, Marcel forced his car by on the outside, sliding wider and wider in the curve until one wheel dipped down into the rain gutter. The car flipped and rolled. Marcel, mortally injured, was dragged out of the wreck and rushed to a hospital. Car after car stopped to help. The other Renault cars, coming upon the wreckage of Marcel's car and learning that their leader was dying, abandoned the race.

As far as Camille du Gast went, she was one of the few drivers to keep her De Dietrich on the road, with some reports claiming she climbed as high as sixth in the overall standings. She sacrificed that position when she came across the wreckage of Phil Stead. Stead was trapped under his car, and du Gast stopped to help him. While Robert Daley claims stead died in the accident, other reports seem to indicate that he survived, thanks almost wholly to the assistance from Camille du Gast. Her decision to stop dropped her to 77th in the final standings, and the race was canceled after just the first of three legs.

I plan to dedicate a full episode to the Paris-Madrid race and its impact on motorsport, but the fallout from this was massive. The French government impounded the cars that competed in the race, as media declared the event “the death of sport racing” and calls for banning motorsport came from far and wide.

After the deadly Paris-Madrid race, du Gast spoke up in defense of racing despite its dangerous nature, and her quotes were reproduced in newspapers around the world in large part thanks to the novelty associated with a woman racing.

In a story titled “Mme. Camille du Gast in Defense of the Devil,” she states:

“Automobile races must not be stopped, but they should be modified. The first and chief danger comes from foolhardy spectators. These people should be prevented from pushing in upon the course. They endanger their lives and those of the automobilists. It is with beating heart I drive my automobile through these crowds through fear of crushing them to death. They gain nothing in pushing in upon the track. They could see just as well if they kept back a reasonable distance.

“I presume we shall have in France very soon a special racing track for automobiles. A large tract of ground will be rented near Bordeaux or some other big city. The machines will run round and round, and people will not be permitted to go in on the track. They will be kept outside as in the case of horse races. Yet I fear too many professionals will be developed, as in the case of bicycling.

I think we might continue to race long distances if ordinary prudence were observed. To stop racing altogether would be a cruel damper upon a great industry and a serious check upon a splendid sport. For my part, I intend to run in every race I can. I am not in the least afraid, and there has been much exaggeration about the recent Paris-Madrid disaster.

“I have just received a letter from Mr. Stead's wife, a pretty American girl, who thanks me for the help I was able to give her wounded husband. If more women took to driving automobiles they would help make the sport more civilized. When I visit America I hope to put their view before your clearsighted women, who are first in every good movement.”

Du Gast was also extremely on the nose in suggesting that permanent tracks would begin to pop up in the future — ones that were dedicated to and maintained for racing, and that would keep spectators at arms’ length. She was smart to point out the letter she got from the wife of the driver she assisted, and to highlight the fact that that woman, for all of her grief, seemed to understand that there would be no stopping anyone from racing — but that she was simply pleased someone had taken a moment to care for an injured person.

Nevertheless, the public backlash to racing was so great after that event that it had an immediate impact: Women were banned from racing by the ACF.

It honestly seems quite shocking that the response to the deaths of what were predominately male competitors was to ban women from motorsport.

While the Paris-Madrid event quickly became a disaster, the issues had nothing to do with women drivers. There wasn't enough infrastructure to manage the event, and it seemed as if those early spectators were unaware of just how dangerous a high-speed racing machine was. According to reports, Charles Jarrott, the first racer to leave the Versailles Gardens, quickly ran upon a group of people clogging the street. He slowed down to give them a chance to get out of the way, but it basically just meant that those folks took their sweet time moving to the side. Add onto that the thick clouds of dust obscuring everyone's vision, and you had a recipe for disaster that had nothing to do with women behind the wheel.

It seems like the race organizers were at an impasse. They had to do something, but it seemed clear that outright banning motorsport as a discipline would be impossible. Over 200 people had entered the Paris-Madrid race boasting all kinds of burgeoning automotive technologies, and it was largely taken for granted that the best way to hone this machinery would be in active competition. The writing was on the wall, predicting the rapid arrival of a horseless age, and if the ACF banned motorsport, then it was extremely likely that racers would simply defect to Germany or Italy to engage in competition.

As a result, women were banned, with the ACF citing “feminine nervousness” as their reason. Thus, there was some kind of “solution” to the problem — even if it wasn't much of a solution at all.

It's not clear how Camille du Gast felt about that ban, though it did dramatically change the course of her career. She'd already impressed the Benz factory team to the point that it offered her a seat in a works car, but that offer fell through when it became clear she wouldn't be legally allowed to race, anyway. Instead, she took advantage of her influence and joined the Automobile Club de France as the first and only female official, even though racing was out of her grasp.

What next? What could satiate her desire for competition? Du Gast turned to an older form of technology that had gained a boost in performance thanks to the evolving technologies brought on by the four-wheeled revolution. Camille du Gast went boat racing.

Camille du Gast: Racing driver

If the public was entranced by the concept of motor racing, then it follows that there was plenty of interest in motor boat racing — particularly because moving these high-speed events away from public roads and into bodies of water meant spectators were largely insulated from any accidents.

Her first boat was named the Darracq, and Camille du Gast cut a striking figure at the helm with her full-length leather coats cinched tight by bustiers, topped off with fashionable hats, gloves, and veils. Her first jaunts took her racing down the Seine in Paris before she headed to Monaco in 1905 to enjoy her first full season of nautical racing.

It was in May of 1905 that she accomplished a frankly stunning feat. Parisian newspaper Le Matin had organized a trans-Mediterranean race from Algiers to Toulon, and Camille du Gast was so determined to win this event that she commissioned the construction of her very own boat, named the Camille, that featured a 43-foot steel hull and a 90-horsepower engine.

On the second leg of that race, from Menorca to Toulon, a massive storm swept over the sea, sinking some competitors and forcing others to seek refuge on nearby military vessels. Even the mighty Camille sank, but because she and her crew had made it the furthest in the event, she was declared the winner. The press dubbed her The Valkyrie of Motorsports, the Amazon, and Gordon Bennett dubbed her the greatest sportswoman of all time.

It isn't clear exactly how du Gast felt about her victory, or her place in the growing boating scene, but it does sound as if she had gotten her fill, because between 1905 and 1912, she instead financed and led five scientific expeditions to Morocco, where she wrote reports on the agriculture and the lifestyle she witnessed there. There was definitely a colonialist attitude in some of her reports, where she expressed a desire to buy agricultural land to teach the Moors how to better cultivate their land, but she seemed to display enough respect for the people she met that they treated her well, and she significantly helped mend political relationships between France and Morocco while also negotiating better access to modern medicine in smaller tribes.

All the while, during her stints at home in Paris, she could be found hosting piano concerts or singing opera, heading off to Sweden or Norway to climb mountains, and competitively riding her horses.

But in 1910, Camille du Gast's life faced a shocking upheaval. Her daughter allegedly attempted to have du Gast murdered.

In Fast Ladies: Female Racing Driver 1888 to 1970, Jean François Bouzanquet writes, “It was her daughter who put an end to this adventurous life. A jealous and mercenary individual, she had been trying for a long time to extort money from her famous mother. By the skin of her teeth, Camille escaped an assassination attempt, instigated by her daughter's ruffian friends, at her home in the middle of the night. She confronted them and they turned tail and fled. Faced with a daughter who had deceived her, nothing was ever the same for Camille after that, and from that point until her death in Paris in April 1942 she devoted herself to her beloved animals.”

Bouzanquet is perhaps a bit melodramatic about du Gast's retreat from public life here. It's true that her daughter's murder plot changed something, encouraging this once-adventurous woman to retreat into a much quieter life — but that isn't to say she disappeared entirely. Instead, she almost wholly devoted herself to charity work, particularly as it pertained to animal welfare.

During the first World War, she established La Reconstitution du Foyer, a charity that provided furniture and household items to people living in towns that had been devastated by battle. She founded a clinic dedicated to caring for pregnant women and new mothers, and created a Relief and Unemployment Fund to battle against the ongoing postwar reception.

Throughout the 1920s, she continued her activism, serving as the chair of the French Society for the Protection of Animals until her death and helping to enlarge and modernize animal shelters throughout France. She was elected president of the SPA by the end of the decade, becoming the first woman to serve in that role, and one of 11 women serving on the 36-seat board. This kicked off a perceived feminization of the animal welfare world, one that coincided with a growing feminist movement that saw women pushing back against rigidly gendered ideas about who should be allowed to compete in sport, and who should be tasked with managing the welfare of marginalized humans as well as animals.

In 1930, du Gast organized a protest against a bullfight in Melun, a commune in France, during which she and several others jumped into the ring, blew whistles, and set off smoke bombs. Over 400 people participated in the demonstration, which forced the bullfight to be canceled. Further, she was a regular activist for the humane killing of animals in Parisian slaughterhouses.

In a November 1932 edition of Le Progrès, a local newspaper, du Gast wrote, “Justice and mercy for animals! Life is difficult for everyone, animals have their share of suffering and they cannot complain! It is up to the hearts of the elite, to the charitable souls, to turn to them and relieve them."

Much of her charitable work, though, seems to have come to an end near the middle of the 1930s, when she seems to fall off the map. Little is known about her later years, aside from the fact that she died in her Parisian home on April 24, 1942. Her cause of death is unknown, but she is interred in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in the Crespin-du Gast family tomb.

Camille du Gast's influence

When I first started writing about motorsport around a decade ago, I really set out to highlight all of the incredible women who had been involved in the motorsport world for over a century, because it felt like that was a critical part of racing history that has been ignored.

Whether it's thanks to a legitimate societal shift or if I've just gotten really familiar with this part of history, it feels like we've moved beyond the common misperception that women were never involved in racing to recognizing that they existed, albeit perhaps as outliers. We have so many great women in and around the sport promoting the accomplishments of women like Michele Mouton and Janet Guthrie and even paying homage to earlier racers like du Gast or Helene van Zuylen.

But personally, I think we're still lacking in context. My goal with this episode of “Deadly Passions, Terrible Joys” is to consider exactly what a woman like Camille du Gast did behind the wheel, and how her career was shaped or limited by ideas of social acceptability. I think particularly with the women who started racing during the Belle Époque, there was this flurry of new technology and new ideas and new pursuits, many of which were still open — they weren't weighed down with, say, masculine associations, and there weren't thick rulebooks dictating your every move. Wealthy, adventurous women like Camille du Gast experimented with motorsport, yes — but it was often one star in a constellation of other interests and activities, as these women tested the waters in hopes of finding a discipline that could be shaped with women in mind. In many cases, they ran headfirst into hastily erected barriers preventing their equal acceptance.

I've gotten comments in the past from people who are like, “why do you keep writing about these women? They weren't world champions. They weren't race winners. They didn't race for their entire lives.” But to me, that misses the point. The fact that these women even turned up on starting grids was impressive. The fact that they could purchase and handle a car was a victory in and of itself. It's easy to forget that we're talking about an era where women could still be considered the property of their male family members and husbands. And for all of the fresh possibilities offered by the new Belle Époque technologies of the time, it was still an era characterized by limitation. Perhaps Camille du Gast never won a motor race — but that's largely because women were banned from racing before they had a chance to do anything.

Women like Camille du Gast saw opportunity in these new technologies and leaped at it. They tried to create a different future for the girls in their lives than they'd had available to them growing up. And even if they didn’t become a world champion or an outstanding winner, they did tangibly move the needle forward when it came to writing the unspoken rules of society that dictated how women could move in the world. That's worth celebrating.

Bibliography

Race to the Future: 8,000 Miles to Paris — The Adventure that Accelerated the Twentieth Century by Kassia St. Clair

Cars at Speed: The Grand Prix Circuit by Robert Daley

Women in Motorsport & social history: Camille du Gast, Bealieu

French Women & Feminists in History: Camille du Gast, Library of Congress

Camille du Gast, The Henry Ford

Camille du Gast, the First Woman to Race Consistently at International Level, Vintage Everyday

Camille du Gast, the Valkyrie of Motorsports, Images Musicales stories

Camille du Gast, Speedqueens

The Belle Epoque and the First World War: Industry, Sport, Utility and Leisure, 1903–1918, French Cycling: A Social and Cultural History

The Fascinating (and Surprising) History of Women Drivers, Culture Study

This Was the Most Beautiful Staircase in Paris, Getting Around with William O’Connor

Auto Racing Endorsed: Mme. Camille Du Gast in Defense of the Devil, The Wichita Eagle

Madame du Gast Believes They Are Good for Women, The Ottawa Journal

The Paris-Berlin Motor Carriage Race, Scientific American

La Femme au Masque: Another Phase, Auckland Star

The Mask Mystery: A Paris Sensation, West Gippsland Gazette

The Masked Woman: Another Phase, West Gippsland Gazette