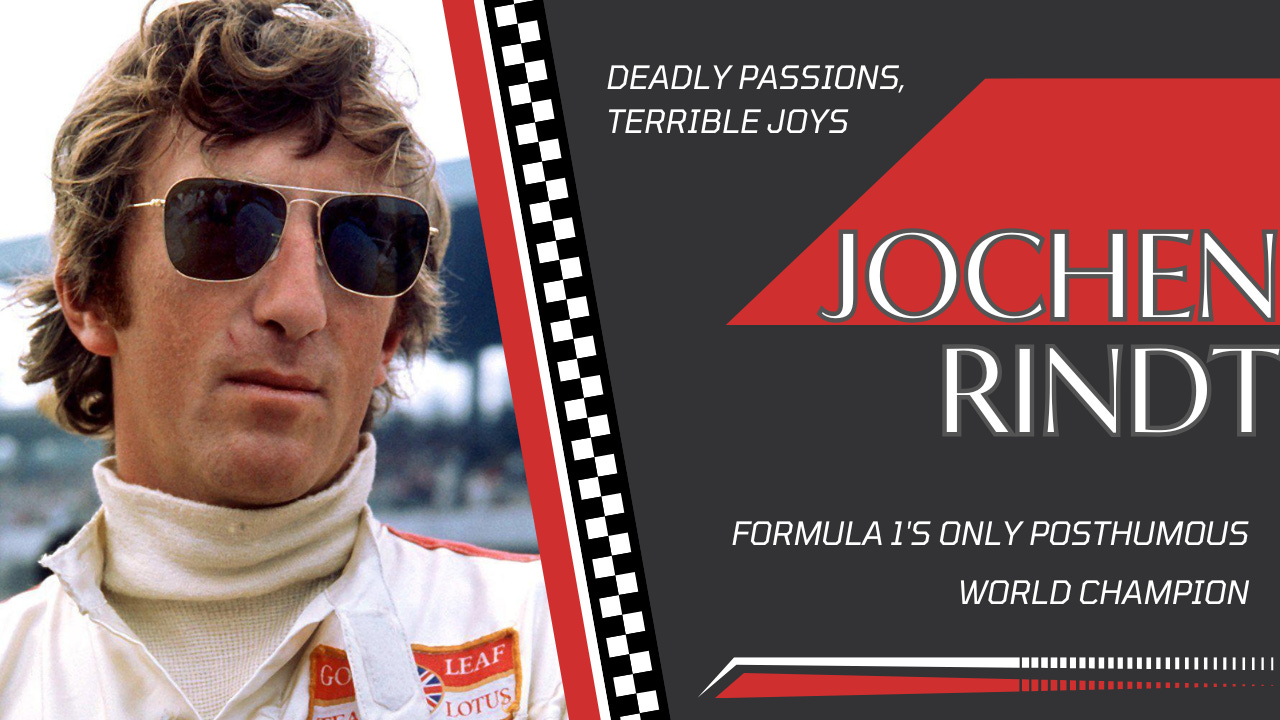

DPTJ Script: Jochen Rindt: The tragedy of Formula 1's only posthumous World Champion

Meet the driver who transformed what it meant to compete in Formula 1.

In 75 years of Formula 1 history, only one driver has been crowned World Champion after his death. In 1970, Austrian racer Jochen Rindt was so dominant behind the wheel of an exceptional car built by Colin Chapman of Team Lotus that no driver could bridge the gap to his place on the top of the championship standings despite there being four races remaining in the season after Rindt's death.

Most F1 fans with any interest in the history of the sport know this — but fewer know the cloud of tragedy that followed Rindt throughout his life, casting dark, dramatic shadows over his every move.

Orphaned at just over a year old, and at odds with his team bosses when it came time to advocate for greater safety, Rindt was a prickly competitor who was nevertheless fondly remembered by so many of his rivals, and who completely changed the name of the game when it came to professionalizing motorsport. Today on Deadly Passions, Terrible Joys, we're going to dig into the ill-fated story of Jochen Rindt's life, the shock of his death, and the legacy he left in his wake.

Jochen Rindt: The birth of a racer

They called it Operation Gomorrah. Together, Britain's Royal Air Force and the United States’ Army Air Forces pinpointed Hamburg, Germany as an ideal target for a major strategic bombing raid in the final week of July in 1943. It remains the heaviest assault in the history of aerial warfare.

Beginning on July 24 and lasting for eight days and seven nights, British forces bombed the city during the day, with Americans taking over during the day. That summer had been uniquely hot and dry in Germany, and as the bombs began to fall and buildings began to flash alight, those conditions were perfect for a firestorm. On the 27th of July, a windless day meant that bombs landed directly on target, with the flames licking straight up into the sky. The heat was so intense that an area of approximately 4.5 square kilometers lit on fire, creating its own pressure system that transformed a whirling updraft of superheated air into a 1,500-foot tall tornado of fire.

At the end of the campaign, over 60% of Hamburg's houses had been destroyed. 37,000 people were killed, with an additional 180,000 injured.

Two of those presumed dead were Karl Rindt and Dr. Ilse Martinowitz. Their 15-month-old son, Karl Jochen Rindt, had been born on April 18, 1942 in Mainz, Germany during the thick of World War II.

His mother, Austrian by birth and one of the original ‘liberated women’ who could often be found ogling sportscars with a cigarette in hand, instilled her love of sport in her infant son thanks to an early career as a tennis player before she followed her own father into law. She'd considered rally racing in her youth, though she'd been discouraged by her family. Rindt's father, from Germany, owned a spice mill. Like his future wife Ilse, he'd dreamed of forging a racing career of his own until familial obligations confined him to safer and more culturally accepted routes. Still, the two had maintained a level of thrilling opposition to the social norms of the time. Ilse had been previously married to a man named Otto Eisleben and had a young son, Uwe, in 1939. But when she met Karl, a pilot who had flown his private plane to Graz, she divorced her husband and wed Karl instead.

In 1942, Ilse and Karl had a child together — a son named Jochen — and the family had evacuated to Bad Ischl, near Salzburg. Sadly, Karl and Ilse Rindt had been called to Hamburg to attend to a business at a local office for the family spice mill. They arrived just in time for the bombing raids; when the two failed to retrieve their son, they were presumed dead, and young Jochen was sent to Graz to live with his maternal grandparents.

Despite having been born in Germany, Rindt would consider himself an Austrian at heart, and it was under Austria's flag that he registered his racing license when his career first kicked off. He had no love lost for the Germans, for whom he blamed the death of his parents.

Even as a young child, it was clear that Jochen Rindt would be quite the handful. He was headstrong from the get-go, just like his mother, and that rebellious streak was regularly indulged by his grandparents. He had little interest in being deskbound at school, but turn him loose on the ski slopes or enter him in a sport, and he positively thrived. When he hit his teenage years, his competitive spirit flourished, and he found himself kicked out of a series of schools in both Austria and England for poor grades and even worse behavior.

Upon losing his seat at school in England and returning to Graz, Rindt met a fellow teenager who would help shape the course of his future: Helmut Marko.

Marko was the son of an electrical dealer who had a need for speed that could only be rivalled by Rindt himself. Their teen years were consumed by trying to acquire ever quicker motorized vehicles — scooters, at first — and taking them to set ever faster laps around the local roads. Before long, the two were expelled from one school and sent off to the mountains to attend a boarding school designed to rid them of their unruly attitudes.

Instead, it gave Rindt his first taste of four wheels.

The boarding house where the boys lived was a half-hour walk from the school grounds — but when Rindt broke his leg while skiing, he requested his grandparents organize a car for him, and he'd find a schoolmate to serve as a chauffeur. It didn't take long before Rindt dismissed the chauffeur and began driving himself everywhere, unbeknownst to his grandparents.

“We had a car, no license, and we managed to go nearly every weekend to Graz, where we had our parties, and there was a good system,” Helmut Marko recalled in Uncrowned King by David Tremayne. “Most of the time we managed someone in the car who had a license and the system was like this; everybody gets a drive, but only as long as he doesn't make a mistake. A mistake means he was not on the limit, so he was judged by all the others. And let's say some wild driving started!”

Rindt was described by friends at the time as being “laddish,” a James Dean-type figure who was always the ringleader of any chaos going on in town. He had an adventurous, rebellious spirit, and on four wheels, he had found freedom.

The moment Jochen had a license, he sourced a second-hand Simca that he began entering local racing events alongside Helmut Marko. In 1961, the two made the trip to the Nurburgring to spectate the German Grand Prix, and Rindt declared confidently that racing Formula 1 cars was exactly what he wanted to do with his life.

After the death of his grandfather, Jochen Rindt was able to convince his grandmother to buy him a brand-new Alfa Romeo Giulietta TI that he had tuned by the best in the business before taking it out to local hillclimbs — first in Austria, then in Germany, before spreading soon into Italy.

In August of 1963, when he turned 21, Rindt came into his full inheritance from his family — $80,000 at the time, which would be the equivalent of more than $800,000 today when adjusted for inflation. He poured that money into his motorsport career, buying a Formula Junior Cooper T59 single-seater car and entering the Italian Formula Junior Championship. Within his first races, he was taking home victories.

From Formula Junior, it was off to Formula Two — but in September of 1963, he made his Formula 1 debut.

That month, a non-championship F1 race had been scheduled at the Zeltweg airfield. Despite the fact that he'd only competed in a handful of open-wheel races by this point, Rindt was determined to compete and borrowed a Cooper T67 from friend Kurt Bardi-Barry to stack up against the likes of Jim Clark, Jack Brabham, and Jo Bonnier. Though his Ford engine failed well before the checkered flag, he had come to a concrete realization.

“It was in 1963 that I recognized that motor racing suited me better than anything else,” Rindt told Austrian journalist Heinz Pruller. “This discovery pleased me, because otherwise I would have wasted two years.”

Even then, Rindt had gained notoriety as a somewhat reckless, on-the-edge racer — albeit one whose audacity behind the wheel promised great things. In one of his debut races at the Flugplatzrennen in 1961, for example, he'd been black-flagged for his dangerous driving style. Completely unaware of what that flag meant, Rindt kept driving like a madman.

There was also the time in a Formula Junior race at Cesentico that an accident resulted in an ambulance racing onto the track. While the competition slowed down for the ambulance, which had parked on the track, Rindt kept his foot to the floor and rocketed between the ambulance and a hay bale to take the lead of the race.

After seeing that, a friend told journalist Helmut Zwickl, "If Jochen Rindt survives, he will be World Champion in two years!”

While it would take longer than two years for the championship to happen, it was an incredibly prescient prediction, because after exactly one year of junior open-wheel racing, Rindt and friend Bardi-Berry decided that it was time to move into Formula Two.

Jochen Rindt's early racing career

With the help of his close friend Kurt Bardi-Barry, Jochen Rindt secured use of a Brabham Formula Two machine to take his professional racing career to the next level, but sadly, the partnership came to an unexpected end in February of 1964. Bardi-Barry was killed in a road accident on his way home from the opera. As such, Rindt's debut in this new category of open-wheel racing came during a race renamed the Bardi-Barry Memorial.

There, Rindt competed alongside talented drivers like Chris Amon, Mike Hailwood, and Peter Revson, albeit with unspectacular results. Following shortly after, though, came a Formula Two event at the Nurburgring that saw Rindt finish fourth, followed by an absolutely shocking victory at Crystal Palace in England.

That win came at the London Trophy event, where Rindt was able to triumph over the likes of Graham Hill — and suddenly, the Austrian's name was on the lips of the continental racing press. Just a few months later in 1964, Rindt was invited to compete in his first 24 Hours of Le Mans with Luigi Chinetti's North American Racing Team, and he made his Formula 1 World Championship debut behind the wheel of a Brabham BT11-BRM fielded by Rob Walker at the unloved Zeltweg Circuit for the inaugural Austrian Grand Prix.

Even though Rindt only managed to qualify thirteenth, and even though he retired from the race, Walker was deeply impressed. The Austrian driver was just 22 years old and already carried himself with an unrefined speed and warmth that promised a great future.

For Walker, it was clear that Rindt was going to be a full-time member of the Formula 1 grid for the 1965 season, but differing sponsorship obligations prevented Walker from being able to offer the Austrian a ride. Instead, it was John Cooper who came calling.

Cooper Cars had been a shining light of the international Grand Prix scene, but by the time Rindt signed on, it was a team on its way down. John Cooper's father died, taking with him the business sense that had made the team financially viable and leaving the team in disarray as it prepared for 1965. The team that once had a reputation for pushing the boundaries of design innovation was instead left to tweak its 1964 designs, hoping its driver pairing of Rindt and Bruce McLaren could bring the cars to success.

That turned out to be impossible. Rindt finished five of the season's 10 races, and his fourth place in Germany and his sixth in America netted him a grand total of four points — good enough for 13th in the World Drivers’ Championship standings. Instead, the Austrian's shining point of the season came with NART at Le Mans, where Rindt and American teammate Masten Gregory powered their Ferrari 250LM to a stunning victory

But there was hope on the horizon. Heading into 1966, Formula 1 introduced a new engine formula that allowed Cooper to mate its decade-old Maserati V12 engines to a brand-new T81 chassis. It wasn't the most groundbreaking evolution in car design, but Cooper knew its machinery would be reliable — and, after countless teams struggling to develop a reliable powerplant, Rindt and new teammate John Surtees were able to dice with the best of them. Rindt snagged two second-place finishes and one third-place in addition to three other points-paying results. At the end of the year, he'd performed well enough to take home third place in the drivers’ standings.

That high would be short lived. Throughout 1967, as Cooper once again faltered, tensions between driver and team grew. Team manager Roy Salvadori snapped at Rindt, accusing him of driving recklessly and with no mechanical sympathy. By the end of the season, Rindt was intentionally over-revving his engines to force failures so he no longer had to drive for the team. That incident took place at Watkins Glen; Salvadori and Rindt decided it'd be best to part ways before that year's finale, the upcoming Mexican Grand Prix.

Rindt's greatest win that season? He married a young Finnish model named Nina Lincoln. Nina's father was a racer, and it was at the track where she and her future husband first met, though their relationship was slow to really kick off. Nina was traveling, modelling, and studying, occasionally turning up at smaller racing events to support her father Curt. She first met Jochen at the track, then really got to know him when the two ended up at the same ski resort in 1963. Four years later, the two had become inseparable and were wed early in the season.

Despite the fact that the relationship with Cooper ended on bad terms, Jochen Rindt was a wanted man. His success in Formula Two was undeniable, and he'd even made a jaunt over to Indianapolis to try his hand at the annual 500. When his services were made available heading into 1968, Rindt received offers from all but two Formula 1 teams.

Rindt knew where he wanted to go: Brabham.

Brabham had won the World Championship in both 1966 and 1967, and Rindt had ample respect for team founder Jack Brabham. But despite that mutual appreciation, the Brabham's Repco V8 engines turned out to be disastrous, and Rindt had little to offer in the way of technical expertise.

Jack Brabham said, “With Jochen, you put the car down and he just drove it. He didn't know anything about the development and he didn't want to know, either. He just had confidence in us, and the way the car was designed and set up.”

Even though the team founder would go on to point out that Rindt was a fantastic driver despite that lack of functional engineering knowledge, it's entirely reasonable to assume that the team could have benefitted from a little extra input on the engineering front.

His best finish of the season was at the year's opening event, the South African Grand Prix, because that race took place so early in the season that the new Brabhams weren't yet ready to be drafted into action. Once the new car was in place, Rindt secured exactly one more podium — but he retired from every single other Grand Prix in 1968.

The relationship between driver and team in this case was fantastic, and Jack Brabham had nothing but compliments to offer the Austrian driver racing alongside him. But already at this point, Rindt was thinking bigger.

He had become close friends with none other than Bernie Ecclestone. Ecclestone would go on to become one of the most influential people in the history of F1, transforming the sport's broadcast rights into a multi-million dollar empire. But in the late 1960s, Ecclestone was a former driver who had realized he'd be better suited leveraging his business acumen in the driver management department. After the death of his original protegé Stuart Lewis-Evans, Ecclestone instead turned his attention to another one of motorsport's rising stars: Jochen Rindt.

But I think it's a little reductive to call Ecclestone nothing but Jochen Rindt's manager. The two were close friends who were equally shrewd when it came to milking the most money out of a situation. That might sound somewhat crass, but motorsport did not pay well back in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Drivers earned a smattering of entry and prize money for competing in Grands Prix, but it wasn't enough to make a living. That's why you had drivers regularly competing in Formula Two, and guys like Rindt heading over to America for the occasional NASCAR race or an entry in the Indy 500. It's also why early sponsorships began to emerge, with drivers aligning themselves with certain tire manufacturers or oil providers in exchange for free products or financial stipends.

Some drivers did enjoy staying active in a variety of disciplines, but Rindt wasn't really one of them. He enjoyed Formula 1, but he despised events like Indianapolis because of their danger. He competed for the money, and that was often it. And while he enjoyed the atmosphere of the Brabham team, he also had grander plans. He wanted to win a World Championship, and he wanted to make money while doing it.

Bernie Ecclestone recalled, “At the end of ‘68 we had the choice for Jochen of the Goodyear deal with Brabham or the Firestone deal with Lotus. I said to him, ‘If you want to win the World Championship, you've got more chance with Lotus than Brabham. If you want to stay alive, you've got more chance with Brabham than Lotus.’ It wasn't a bad thing to say; it was a matter of fact.”

Rindt made the call. He wanted that championship, and he opted for Lotus. Ecclestone stepped in to help negotiate a handsome deal.

But that question of survival at Lotus was a major concern.

Jochen Rindt's move to Team Lotus

For all of its success, Team Lotus came with a reputation. It was quick and audacious, but that boundary pushing came at the expense of safety.

The story of Team Lotus starts with founder Colin Chapman's desire to build ever quicker cars, which he summed up in one very simple statement: “Adding power makes you faster on the straights. Subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere.”

That sounds like common sense to us today, but at the time, overall speed was thought to be most closely associated with power, and to support that power, many carmakers felt it was necessary to build more robust machines. A car with a more powerful engine needed to be strong enough to cope with the added weight and stress associated with that engine, and that often meant those cars should be heavier, more rigid, and bigger all around.

Chapman turned that logic on his head. A student of structural engineering at the University College London and a pilot at the University of London Air Squadron, Chapman saw how many of the advancements in flight could be associated with lighter and more agile planes, not exclusively through more powerful engines. And after he founded Team Lotus and began building Formula 1 cars, that mindset became ever clearer.

In 1962, for example, Chapman introduced the Lotus 25, which featured the first fully stressed monocoque chassis in Formula 1 history. By combining various chassis panels into one cohesive unit, the Lotus 25 was therefore lighter and more rigid than the cars around it. Further innovations included introducing the car's engine as a stressed member of the chassis in the Lotus 49. That, too, set the standard for open-wheel car construction for quite literally the rest of history.

But those were Chapman's successes. There was plenty of experimentation that failed to pan out, resulting in retirements, crashes, and general failures, and countless drivers were seriously injured or killed behind the wheel of a Lotus — Stirling Moss, Alan Stacey, Mike Taylor, Mike Spence, Bobby Marshman. Even the seemingly invincible Jim Clark lost his life driving a Lotus machine in a Formula Two race the year before Jochen Rindt joined the team.

Jochen Rindt had a very strange relationship with Team Lotus founder Colin Chapman. As a driver, he keenly understood the risks associated with Lotus, a team that was known for developing unreliable cars that, in a 21-month period between 1967 and 1969, crashed a whopping 31 times. As fellow Lotus driver Graham Hill liked to quip, “Every time I'm being overtaken by my own wheel, I know I'm in a Lotus.”

But it was Lotus which Rindt felt would give him the best shot at glory. From the very beginning, the Austrian driver was quoted as saying, “At Lotus, I can either be World Champion or die.”

His education in the art of Team Lotus kicked off early, as Rindt and teammate Graham Hill were sent off to New Zealand and Australia to compete in the Tasman Series. It was there that Rindt had his first major accident behind the wheel of a Chapman-produced car; during the Rothmans International race at Levin, Rindt flew off the track and plowed into an earth embankment. His Lotus flipped, and he was briefly trapped beneath it until a few local racers rushed to the scene. One pushed the Lotus up just enough for another driver to pull Rindt free. He was unhurt, but it was a very early lesson in the goings-on of his new team.

The Formula 1 season officially got underway in March at Kyalami, where Rindt was quick but was forced to watch his old Brabham team snatch victory from the sidelines, his Lotus 49B having retired. He found somewhat more success at the BRDC International Trophy at Brands Hatch, a non-championship race where he finished second. But things were about to take a shocking turn.

Heading into the 1969 Spanish Grand Prix at Montjuich Park, Colin Chapman had had a bold idea. He was one of several team bosses who had fitted his race cars with wings that were mounted on the suspension. They were awkward things, with the rear wing in particular mounted on struts several feet above the chassis — and Rindt was no fan.

Speaking to journalist Mike Doodson at Motoring News, Rindt was firmly anti-wing, saying, “Wings are very dangerous because sooner or later, if wings get any bigger and the car happens to get into a spin, the air flow is reversed and the rear of the car will lift off.”

It's worth noting that that kind of lift-off wouldn't actually really be possible, not the way Rindt described it. But he was adamant that wings should be banned.

“One of the reasons that a bad car can handle well these days is because of wings,” Rindt argued. “If you have a bad car, the design is really rather unimportant when you have the advantage of a big wing. In other words, wing development threatens to become much more important than chassis development as we have come to know it.”

The article was published just before the build-up to the Spanish Grand Prix, and Colin Chapman was furious — to the extent that he effectively gave Graham Hill talking points on wings to share in his interviews.

A member of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association, Rindt was one of the men tasked with investigating the circuit's safety and found that Montjuich Park had failed to erect the proper guardrails; what existed were simply too low. Race organizers were forced to make the changes, and come race day, Rindt bolted into the lead at the drop of the flag, hoping to secure his very first Grand Prix victory.

Then, not long after, Graham Hill felt something break on his Lotus, which sent him flying into the guardrails at a corner just past the pits. Lotus mechanics raced to the scene to find Hill unhurt, but a quick look at the wreckage caused them to wonder if the rear wing hadn't failed. A mechanic rushed to the pits to tell Chapman to bring Rindt in, but he was too late.

Heading into the 20th lap of the race with a stunning eight-second lead, Rindt's rear wing also snapped and sent his Lotus careening directly into the wreckage of his teammate's car. Again, miraculously, the driver escaped with nothing but a broken nose. The taller trackside barriers had prevented both Lotuses from escaping further into the crowd, and only a marshal was injured.

Rindt spent four days in the hospital and pointed out that he felt extremely dizzy for a week after the wreck. He skipped the Monaco Grand Prix (though he did compete at the Indianapolis 500 shortly after).

After that Montjuich Park accident, Rindt was irate. His worst fears about Colin Chapman had been proven correct, and he didn't hesitate to point the finger squarely at the Lotus boss.

“I place the blame on [Chapman] and rightfully so, because he should have calculated that the wing would break,” Rindt raved to a reporter after the crash.

Several days later, speaking to Austrian television, he added, “These wings are insanity in my eyes and should not be allowed on racing cars. But to get any wisdom into Colin Chapman's head is impossible.”

He was asked if he trusted Lotus after the accident, to which he responded, “I never had any trust in Lotus.”

On May 9, 1969, Jochen Rindt penned a letter to boss Colin Chapman at the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge in Indianapolis. In it, he wrote:

Dear Colin,

I just got back to Geneva and I am going to have a second opinion on the state of my head tomorrow. Personally I feel very weak and ill, I still have to lay down most of the day. After seeing the new Doktor and hearing his opinion, we can make a final decision on Monaco and Indy.

I got hold of this incredible picture which pretty much explains the accident, I didn't know it would fly that high. Robin Herd apparently saw the wing go, but could not see the accident, since it happened around the corner.

Now to the whole situation, Colin, I have been racing F1 for 5 years and I have made one mistake (I rammed Chris Amon in Clermont Ferrand) and I had one accident in Zandvoort due to gearselektion failure otherwise I managed to stay out of trouble. This situation changed rapidly since I joined your team, Levin, Eifelrace F2 wishbones and now Barcelona.

Honestly your cars are so quick that we would still be competitive with a few extra pounds used to make the weakest parts stronger, on top of that I think you out to spend some time checking what your different employees are doing, I'm sure the wishbones on the F2 car would have looked different. Please give my suggestions some thought, I can only drive a car in which I have some confidence, and I feel the point of no confidence is quite near.

Best regards

Colin Chapman couldn't believe it. Never before had one of his drivers so publicly spoken out against him.

Dick Scammell, racing manager at Team Lotus, recalled, “I think Chapman was quite used to people doing what he asked them to do or he just got rid of them, whereas Jochen was good enough that he couldn't get rid of him, so he had to bend over a bit for him and allow him to do things.”

The two men, furious, refused to speak to one another directly. If Rindt needed to get a message to Chapman, he'd ask Bernie Ecclestone to send it over. Meanwhile, if Chapman wanted to talk to Rindt, he'd ask journalist Jabby Crombac to pass on the information.

Making matters even worse was the fact that stilt-mounted wings were banned before the Monaco Grand Prix, though, ultimately, Graham Hill would go on to take victory. By the end of the season, aerodynamic devices were allowed if they were fixed to the bodywork, not the suspension, and if they were unable to move.

During practice for the Dutch Grand Prix, Lotus debuted its Lotus 63, an experimental four-wheel drive race car that Graham Hill labeled a “death trap” and that Rindt adamantly refused to drive. Again, Chapman was irate; he felt that the 63 represented a major leap forward in motorsport design, and once again, it was his new driver who was raising a stink.

Rindt retired from the Dutch and French Grands Prix, then took a fourth-place finish at Silverstone. Another retirement at the German Grand Prix followed — but things began to turn around within the Lotus organization. Rindt and Chapman hashed out their problems in a marathon meeting that weekend and ultimately emerged with a tenuous truce that meant they could once again speak directly to one another.

But Rindt still wasn't pleased, not completely. He was toying with the idea of returning to Brabham, feeling like his bad luck at Lotus would mark an early end to his racing career. He and Bernie Ecclestone were also making grand plans to start their very own Formula 1 team, which would get its start as Jochen Rindt Racing in Formula Two. Those concerns, though, were pushed to the side as luck began to favor Rindt once again.

At the Italian Grand Prix at Monza, Rindt flashed across the finish line in second, just eight-hundredths of a second behind winner Jackie Stewart, who was crowned World Champion.

The F1 circus then moved off to Canada, where Rindt took another podium, albeit in third place. And then, at the US Grand Prix, the Austrian driver looked unstoppable. He set the weekend's fastest lap to secure pole position and, though he ultimately lost the lead to Jackie Stewart on Lap 12, he was able to reassume the lead when the Scot retired. In the closing stages of the race, his engine sounded sicker and sicker, but Rindt held out and crossed the line a winner — his first-ever victory in the Formula 1 championship.

That the Mexican Grand Prix ended in a retirement hardly mattered. Rindt had secured 22 points to finish fourth in the World Drivers’ Championship standings, and the future seemed bright. After fielding offers from other teams — and after even inking an early contract with Brabham — Rindt ultimately made the decision that his best shot at winning a championship would lie with Lotus. He inked a one-year extension with Chapman, and at the end of the year, during a dinner with a journalist, Rindt reflected, “In 1970, I want to be World Champion and the biggest name in motor racing. But racing will only be a part of my life. When I have the title, I am going to retire immediately. I just don't want to be finished and exhausted before I am 30 and just carry on racing because there is nothing else I want, can do, or am interested in. There are so many things which I would like to do. Time is the most valuable thing you can have. And listen: I will be living another, say, 50 years. But I have taken out from 28 years more than you can usually gain. Isn't that simple to understand?”

Rindt went on to argue that there were only two true professional drivers competing in Formula 1: Himself and Tyrrell driver Jackie Stewart, because both of them “drive with our heads.”

Such was the tone set heading into the 1970 Formula 1 season, which admittedly started off on the wrong foot. Lotus’ latest challenger, the 72, was not ready to compete by the start of the year, which meant Rindt was once again piloting the aging 49 — but when the 72 made its debut in Spain, it simply didn't work.

Chief mechanic and team manager Dick Scammell explained that the 72 was “a horrendous car to begin with, with that anti-squat and anti-dive on it. No feel on it at all. The drivers needed the feel, for the car to move a bit.”

Even worse, a front brake failure saw Rindt narrowly avoid colliding with the barriers. His fear was clear, even as he returned to the pits and shouted at Chapman, “I'll never sit in that fucking car again as long as I live.”

While Rindt did indeed compete with the 72 in the race itself — which ended in retirement — he refused to consider driving it again until its major issues were worked out. That meant that, for both the Monaco and Belgian Grands Prix, the Austrian was back behind the wheel of his 49C.

In Monaco, it was a fruitful choice: Rindt had a poor start but when the competition began retiring one after another, and as he began finding the pace to pass the rest, Rindt took victory on a chaotic final lap that saw him make a daring pass for the lead.

The Belgian Grand Prix ended in a retirement, but that was no matter. The revamped Lotus 72, now known as the 72C, was ready to make its debut.

This machine featured a stiffer monocoque and had completely eliminated the anti-dive and anti-squat components of the suspension that had made it so challenging to drive. It was a sensitive, responsive car, and in his first flying laps around the Zandvoort circuit, Rindt crushed the previous lap record by a whopping seven seconds.

Come race day, Rindt would begin a glorious winning streak that would launch him from fourth in the championship standings to a dominant first. He won at Zandvoort, then in France, then in England, and then in Germany. Come the conclusion of August's event at the Nurburgring, Rindt had 45 points. The next closest competitor, Jack Brabham, was 20 points behind.

During his home race, Rindt suffered a retirement — but in some ways, that was no matter. With just four grands prix remaining in the 1970 season and a dominant car beneath him, Rindt felt confident that he had all the tools he needed to cruise to his first title.

But first, he would need to conquer the 1970 Italian Grand Prix.

Jochen Rindt's death

As Jochen Rindt came ever closer to securing his first World Championship, the question of retirement loomed over him, encouraged in many ways by his wife Nina.

1970 had been the kind of year that would shatter the determination of even the bravest of drivers. At the start of June, Bruce McLaren was killed testing a Can-Am race car at Goodwood. Much like Jim Clark, McLaren was one of those drivers whose deaths felt impossible; the Kiwi had been talking about retirement, about transitioning into running his race teams rather than competing for them. And in a flash, he was dead.

Then, three weeks later, Piers Courage was killed.

Courage and Rindt had become close. Their wives, Sally and Nina, were practically inseparable, and the couples could regularly be found in one another's company — often with the inclusion of Jackie and Helen Stewart.

But on June 21, at the Dutch Grand Prix, Courage made contact with Lotus driver John Miles, and Courage's car burst into flames. The wreck had happened on Lap 23 of 90, and in those days, races weren't flagged for death. Instead, the race continued, with Jochen Rindt taking a decisive victory upon the debut of the innovative Lotus 72.

“I saw the burning, and I saw Piers’ helmet very near to it,” Rindt reflected after the event. “For some laps I desperately hoped that he had climbed out and thrown away his helmet, but then I realized that Piers, if he had come out, would never have put his helmet down so near the car.”

His friend was dead.

Rindt crossed the finish line with a monstrous 30-second lead. There, he received the news that Courage had been killed in the accident and that Nina had immediately rushed to Sally Courage's side. The two women left the race track together.

“It was odd,” Nina recalled, “but I was angry that Jochen won. It was sort of, ‘How could he win the race in which Piers was killed?’ It was all just so horrific, so disgusting. I was very angry, though not really at Jochen. I was just angry at the whole thing.”

That bevy of emotion was present on the race winner's face as he stood on the podium wrapped in the victor's laurels. In an interview immediately following the race, he said, “That somebody is lost in this sport is nothing new, but it is bitter indeed when it happens to be your friend.”

When Rindt began the journey home alongside Bernie Ecclestone, the question of retirement weighed heavily on his mind. The sudden death of one of his closest friends sent him reeling — but for the first time in his career, he had a car that wasn't just capable of winning races but of dominating them. He was one point behind Jackie Stewart in the championship standings, and if the Lotus 72 continued to perform, he could almost guarantee a title come the close of the season.

But as he ultimately told both Ecclestone and Nina: “If I want to keep my self-respect, I can't quit during the season.”

It was not an easy decision to make. In The Uncrowned King, Nina Rindt reflected on the impact of Courage's death, and why it felt so different from the deaths of other drivers — and I want to read that quote here in full.

“I guess the thing was that Piers dying showed that it could happen. When Jimmy [Clark] died, Jochen was shattered. But I sort of pushed it away. I told myself it was a fluke, it couldn't happen to Jochen. I was brought up with racing because of my father, and I never regarded it as dangerous. When you are a young person, you just push danger away, don't you? Or you couldn't survive.

“When it was Piers, when I saw Sally and the kids, I realized that it was really serious. We took her home in Bernie's plane, and then Jochen and I stayed with Bernie and Kwana at his place. I completely collapsed when we got there. Jochen was angry with me. ‘You have to come down for dinner!’ But I just lay there. How could anyone care about dinner?”

But Courage's death wasn't the only one on Rindt's mind. The couple had become close skiing friends with a man named Ernst Moorsbrucker, the nephew of the owner of the hotel where they were staying over 1969's holiday season. After they departed, Moorsbrucker was diagnosed with cancer. Weeks later, he was dead.

Nina revealed that Rindt was consumed with worry, asking himself, “Is it better to die the way Ernst did, or to die instantly, like Piers?”

“He thought perhaps it was better to go like Piers.”

The day of Courage's funeral, the racing contingent quickly traded their mourning gear for racing overalls and jetted off to Rouen for a Formula Two race. There, in the Formula 3 support event, two young drivers were killed in separate incidents. The racing world was seemingly plagued by death, and Nina was firmly convinced that her husband could seriously consider stepping away before it was too late.

The primary problem was that Rindt firmly believed he was only just beginning to crack the code of being a modern racing driver — one who was not only successful on the track but who fostered a variety of commercial interests outside of the cockpit. He and Bernie Ecclestone had established Jochen Rindt Racing, a successful Formula Two team that looked poised to break into Formula 1 in the near future. He'd put up his own money to establish the Jochen Rindt Motor Show, almost singlehandedly developing a healthy appreciation of racing in his home country.

He was also keenly aware of the fact that Formula 1 was becoming ever more lucrative, and as World Champion, he'd be able to command greater entry fees from race organizers. And as he arrived in Monza for what could be the championship decider, he was weighing up several options for the future.

Jochen Rindt was thinking about retiring immediately; he'd seen the way the death of Piers Courage wracked the man's family as well as the racing world as a whole, and he knew that his Lotus put him in greater danger than some of the slower but more robustly built machines on the grid.

He also considered competing for one more year in F1 — to effectively take a victory lap, sweeping up money from entry fees and promotional stints. And if that worked well, maybe he'd hold out for a second year. He could see the tides turning, could see the money to be made. He was hesitant to step away just before the sport became deeply professionalized.

But other opportunities arose. Despite the fact that he had not enjoyed his first attempt at NASCAR, a weekend spent with Bill France had convinced him that there was way more money to make in American stock car racing than in Grand Prix racing — and the enclosed nature of the cars made them much safer. Everyone who knew Rindt at the time had a very different idea of what he'd have done after winning his title, and that was largely because he was changing his mind on an almost hourly basis.

This was the background noise accompanying Jochen Rindt's fated trip to Monza for the 1970 Italian Grand Prix.

That weekend, Lotus brought with it a brand-new chassis, the Lotus 72/5. This was the machine that Rindt was expected to use in the grand prix, once a young rising star named Emerson Fittipaldi had completed shaking it down to guarantee it was fit to race.

But in practice, Fittipaldi wrecked that new chassis. He collided with Ignazio Giunti's Ferrari in the Parabolica after locking up. Fittipaldi rode his Lotus overtop the Ferrari, then ended up colliding with a tree outside of the race track. He was unharmed, but the Lotus 72/5 was damaged.

That left Jochen Rindt with the older but still successful chassis, the 72/2, to utilize in practice and the race.

The Austrian driver had requested his team remove the wings, believing that the wing-free car would be quicker, even if it would be more difficult to handle. When he reported an additional 800 rpm without the drag of the rear wing, Chapman OK'd the decision, even as one of Lotus’ third drivers John Miles reported that just one lap in a wingless Lotus “was enough to convince me that my car was undriveable.”

The first day of practice, September 4, went off without any hitch but Fittipaldi's crash. Leaving the track, Nina Rindt remembers that, unprompted, her husband turned to her and exclaimed, “I feel wonderful.”

September 5 brought with it final practice, and the quickest times of the day would set the grid. Colin Chapman had ordered Rindt's Lotus undergo an engine change overnight, with the newly fitted engine capable of a 205-mph top gear designed to set pole position. Thanks to the slipstreaming nature of the event, though, Rindt wasn't quite as concerned about securing pole as he might have been at other tracks. He simply climbed into the cockpit of his Lotus 72 that afternoon and told journalist Heinz Pruller, “I must go.”

Rindt turned one lap at Monza, then two, three, and four. Team Lotus awaited the glimmer of his red-and-gold machine flitting by for its fifth circuit. The car never returned to the pits. Instead, soon after, Denny Hulme cruised slowly into Lotus’ pit stall to report that there had been an accident.

Jackie Stewart recalled that, slowly, the track grew silent as more and more drivers returned to the pits. He heard directly from Hulme that there had been an accident, and he went directly to race control to inquire after the wellbeing of his friend — but in Italy, there were no straight answers. No one would definitively state anything other than the fact that Rindt was out of his car.

Hulme had been hot on Rindt's heels at the time of the accident. Asked about it after the fact, he explained, “Jochen was following me for several laps and slowly catching me up and I didn't go through the second Lesmo corner very quick so I pulled to the one side and let Jochen past me and then I followed him down into the Parabolica, ... we were going very fast and he waited until about the 200 metres to put on the brakes. The car just sort of went to the right and then it turned to the left and turned out to the right again and then suddenly just went very quickly left into the guardrail.”

Trackside personnel brought Rindt back to the paddock in the bed of a pickup truck. Stewart was one of the first drivers to lay eyes on him, remembering, “Jochen was just lying there, on his own. I will never forget that. There was nobody else there. I could immediately see that his ankles were very badly damaged, but there was no bleeding. If there is no bleeding it means the heart is not pumping. A priest came to give him the last rites while I was still there. I walked away knowing for myself that Jochen was not coming back. Nina, Helen, Bernie, and Colin went to the hospital, each at that point believing that he was still alive. In Italy they never pronounced a driver dead at the scene of an accident, otherwise they would have to call off the event. Always they would say that they died on the way to the hospital, but I had seen Jochen's feet. I knew.”

Nina Rindt recalled that, in the silence of the paddock, Colin Chapman informed her that Jochen had spun. Believing it to be a routine racing incident, she set her stopwatch aside to take a break from scoring her husband's laps. Then, someone ran up to tell her that they'd escort her to the medical center.

Confused, Nina went; when she arrived, Jackie Stewart tried to tell her that her husband was okay, but she recalled seeing how pale he was, trembling as he delivered the news. No one would allow her to enter the ambulance as it took Jochen away. Then, she spied a priest leaving the medical center, who told her to have courage.

Looking around, Nina Rindt realized that everyone was staring at her. She recognized those looks; she'd seen those same expressions gazing at Sally Courage after Piers was killed. Noting that, she recalled, “I knew that something very bad had indeed happened. I could see that from the faces all around me.”

She allowed herself to be driven to the hospital, where she received the news straight from Bernie Ecclestone: "Jochen is dead.”

Once it was clear that Rindt's crash had been fatal, the members of Team Lotus set to work. In Italy, law dictates that for every death, there must be someone responsible — and in motorsport, that often meant the team boss, designers, and mechanics could be arrested, with all the team equipment and cars impounded by police. Lotus had experienced this before, back in 1961, when Jim Clark was involved in the incident that killed Ferrari driver and championship contender Wolfgang von Trips.

The crew leaped into action. Colin Chapman and Nina Rindt were ushered to private planes that flew them out of Italy, while back at the track, Lotus mechanics made quick work of tearing down their garage area, packing up the cars, and fleeing to the border. Allegedly, one member of the team dressed up in a disguise in order to retrieve the engine and gearbox from a locked room at Monza, though no one can quite remember if that was true.

In the aftermath, Nina Rindt recalled, “It sounds really weird, but I was less shocked by Jochen's death than I was by Piers'. They were so close together. I wasn't surprised anymore. I had lived through so much by then. The first time it was really, ‘My God, it can actually happen.’ You're so young, so stupid, you have this defense and you don't think about it. And I don't think Sally did, either. I was in shock, but maybe not as much as I would have been if Piers had not died.”

But for the rest of the Formula 1 field, things returned to normal. As soon as the ambulance left the grounds, Jackie Stewart climbed back into his Tyrrell to qualify for the Italian Grand Prix. He turned a quick lap, able to compartmentalize the loss of his friend — but when he was handed a glass bottle of Coca-Cola after climbing out of the car, he smashed it against the wall.

“I was so angry at the stupidity of his death, that his life had been taken just like that,” he remembered. “I felt completely empty, drained, and exhausted. I felt capable of nothing, and absolutely lost.”

But the race went on. Ferrari's Clay Regazzoni qualified on pole, and he went on to secure his maiden Grand Prix victory in front of a crowd of overjoyed Italian fans. They had already put the tragedy of Jochen Rindt's death behind them.

Not long after, the racing contingent somberly made their way to Rindt's funeral in Graz, and Swedish racer Jo Bonnier was tasked with delivering a eulogy he likely never expected to write.

“To die doing something that you loved to do, is to die happy,” Bonnier said. “And Jochen has the admiration and the respect of all of us. The only way you can admire and respect a great driver and friend. Regardless of what happens in the remaining Grands Prix this year, to all of us, Jochen is the real world champion.”

Despite the fact that a major investigation into the crash was carried out by a group of PR men titled Grand Prix Accident Survey, there's never been a consensus about what, exactly, caused Jochen Rindt to spin. Some people have suggested that the right front brakeshaft had sheared under heavy braking, while others believe the removal of the wings caused the car to become violently unstable at high speeds.

The 1972 Grand Prix Accident Survey described the crash itself in major detail, explaining exactly what happened to Rindt once his Lotus was out of control. But there was no way to inspect the damage and pinpoint what could have caused the accident, and what was instead damage sustained during the wreck itself.

Colin Chapman, too, picked up the pen to craft a lengthy defense of Lotus’ manufacturing techniques, using evidence to refute claims that the suspension had snapped, that mechanical failure took place, that the construction of things like brakes were shoddy. He described how Lotus had investigated all of the questionable parts and found nothing terribly wrong, nothing to indicate a failure.

The cause of Jochen Rindt’s death, however, is clear. His lap belt caused major injuries to his chest, neck, and spine. When the front of his Lotus was ripped away, the centrifugal force caused by the spinning car sucked Rindt out of the hole in the cockpit.

Rindt had only partially secured his lap belt. He preferred to use only the lap belt. He never used the crotch strap. Had he done so, it is widely believed that Rindt would have remained in the cockpit of his Lotus. He would not have slid out of the hole in the front of the car. He very likely would have suffered injuries, but he would not have been strangled to death by his own lap belt. Jochen Rindt would have lived.

The fallout

Having been killed before the Italian Grand Prix, there would be four races remaining in the 1970 Formula 1 World Championship — four more opportunities for another driver to snatch the title.

Admittedly, it seemed unlikely. After the Austrian Grand Prix just weeks before Jochen Rindt's death, he remained firmly in the lead of the drivers’ championship with a whopping 45 points to his name. His next closest challenger was Jack Brabham, who boasted 25 points, followed by Denny Hulme with 20.

But it would be Jacky Ickx — winner of the 1970 Austrian race — who would begin to mount a strong challenge.

Victory in Austria marked a turning point in Ickx's season with a challenging Ferrari, and he rocketed three positions up the standings with a total of 19 points, tied with Jackie Stewart for fourth overall.

By finishing second in Italy, Stewart ascended to 25 points in the championship, and Ickx once again fell back. Then, however, the F1 circus returned to North America for the Canadian Grand Prix. Ickx mastered the Mont-Tremblant Circuit to take another victory, netting him 28 points to Rindt's 45.

Heading to the next event, the US Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, Ickx once again looked to be dominant. He was quickest of all the drivers in Friday practice, and a sudden rainstorm partway through qualifying on Saturday meant no one was able to unseat him at the top of the charts. If Ickx could hold onto that lead through to the end, he'd chop down the gap to Rindt — and though he'd have to count on a win at the season finale in Mexico to take the title, there was still a shot.

It was a shot that slipped away with a broken fuel line. On Lap 57 of 108, Ickx darted into the pits for repairs, trading his second place in the running order for 12th on the charts. By the end of the race, he'd managed to wend his way up to an impressive fourth-place finish, but it wasn't enough. He needed that win. Without it, the title would be decisively handed to the late Jochen Rindt.

In The Uncrowned King, Ickx is painted as something of an antagonist. While Jacky firmly denies that he ever had harsh words with Jochen, many of Rindt's friends believed that he grew frustrated with Ickx's pushing back against improved safety standards — and, further, that much of the Grand Prix field was going to make an active effort to prevent Ickx's title charge should it look like he was about to snatch the crown.

In the end, it wouldn't matter. The Ferrari driver went on to win the season finale in Mexico City, ending the season with 40 points — five shy of Jochen Rindt.

There's a myth that has built momentum over the years, one that says the fuel line problem in Watkins Glen was a fabrication, or that it was perhaps sabotage. This largely seems to have been strung together thanks to some choice translations from interviews on Belgian television, where Ickx said it would have been very convenient if the fuel line had broken. More than anything, though, I think this myth found footing because Jacky Ickx has repeatedly said he didn't want to win the World Championship.

Perhaps this is a bit of creative shading in hindsight on Ickx's part, but over the years, he has maintained that he never cared about championships, and that winning it in 1970 would have been a particularly hollow victory. But I don't think there was any intention to throw the championship.

I want to quote Ickx from a 2020 interview he gave to Autosport, where he said, “First of all, honestly, the world championship had no meaning for me - the goal was always to win races, not calculate how many points I would get for this position or that.

"Still, this was a horrible situation. I was obliged to try and win for Ferrari if not for myself, and if I won the last three races I would be champion, by one point. I won at St Jovite, but then had a problem at Watkins Glen and finished fourth.

"That was a huge release. I didn't want to be champion, beating a man who... wasn't there any more. Where would have been the glory in that? Jochen deserved the championship - if God exists, he made the right decision. I went to the last race, in Mexico, in a good frame of mind. And I won again."

At the official awards ceremony at the end of the year, Jochen Rindt's championship trophy was handed to his widowed wife, Nina. From there, she went on to complete his remaining obligations, turning up at the Jochen Rindt Auto Show, where fans asked her for her autograph in the midst of her grief.

“I was convinced by the people who were involved in its organization to do it in Jochen's name,” she remembered in The Uncrowned King. “It was terrible. I was on tranquilizers. I wasn't coping very well. There were photos of Jochen everywhere, and people wanting my autograph. Like I was the star… What had I ever done? I kept asking myself, ‘What do these people want from me?’ It was absolutely awful, just too much. I completely broke down, but behind closed doors.”

Years later, she gave up the naming rights to the exhibition, which became known as the Essen Motor Show — because at that point, Nina Rindt asked, “What did the Jochen Rindt bit mean?”

Jochen Rindt was just 28 years old when he died, and in so many ways, his best years were still in front of him. He had a stunning talent behind the wheel, yes, but it's extremely likely that his greatest successes would have come from outside the cockpit.

Rindt's closest friend and confidante was none other than Bernie Ecclestone. At the time, Ecclestone was a failed racer who had instead turned to the business side of motorsport, but it wouldn't take long before he would become a transformative player in the tides of Formula 1 history. He would go on to buy the Brabham team, to advocate for better terms of competition for British F1 teams via the Formula One Constructors’ Association, and to ultimately take hold of the sport's commercial rights. When he finally sold off those rights in 2017, they were worth a whopping $8 billion.

Given that Ecclestone and Rindt were already dreaming up plans to go into business together, it's easy to imagine that the Austrian racer would have become a major player in the ever-changing tides of F1 in just the same way Ecclestone was. Rindt had an eye for opportunity and wasn't one to shy away from a lucrative deal. More than that, he was never afraid to make his true feelings known, even if that meant writing op-eds about his boss’ dangerous car design habits in major motorsport publications. Imagine his influence on the trajectory of motorsport if Jochen Rindt had lived and brought that same attitude to bear on the running of F1. Imagine what the safety crusade of the 1970s might have looked like. Imagine the commercial deals he could have organized. Imagine the promotional power of a former World Champion who instead dedicated himself to improving the function of motorsport.

Unfortunately, all we can do is imagine, because on September 5, 1970, one of motorsport's most promising talents lost his life at Monza.

I still vividly remember watching the 1970 Monaco Grand Prix with my dad via tape delay on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. They had a camera at the last corner where Brabham’s brakes failed and he went head on into the barrier allowing Rindt to sneak by for the win.