Happy 75th birthday, Formula 1!

On May 13, 1950, the first-ever F1 World Championship race took place at Silverstone. While Formula 1 (as a regulatory set dictating how cars could be prepared) had been first founded in 1946, the 1950 British Grand Prix was the first ever championship race. So, while the occasional F1 event may have taken place prior to 1950, those events weren't linked together into any cohesive championship.

But heading into 1950, the FIA wanted to reintroduce the pre-war European Drivers’ Championship, but on a bigger scale. It wanted to crown a World Champion. And so, a seven-race calendar was drafted together.

This calendar consisted of six of the most iconic European Grands Prix in existence — in England, Monaco, Switzerland, Belgium, France, and Italy. In order to qualify the sport as a ‘World’ Championship, though, the FIA knew it needed to tack on a non-European race. The most prestigious at the time was the Indianapolis 500; the FIA had ties to the AAA, which sanctioned the 500 at the time, and used those connections to add the Greatest Spectacle in Racing to the F1 calendar through 1960. (Only one F1 driver ever raced in the 500 during that time.)

Oh, and the points system was also wild!

1st place: 8 points

2nd place: 6 points

3rd place: 4 points

4th place: 3 points

5th place: 2 points

Fastest lap: 1 point

Only four of the seven races could be counted toward your championship total, so if you had a bad weekend (or, y'know, skipped the Indy 500), then you'd still have a chance to crush it for the rest of the year.

Alright — backstory out of the way! Let's get stuck into the 1950 British Grand Prix, shall we!

The Manufacturers

Alfa Romeo (Italy)

Maserati (Italy)

ERA (UK)

Alta (UK)

Talbot-Lago (France)

Notably absent from the first official Formula 1 World Championship Grand Prix was Ferrari. At that time, individual race organizers were in charge of entry and prize money distribution, and ol’ Enzo wasn't happy with the piddling amount he was being paid. The Scuderia would make its grand debut at the next race, Monaco.

The Drivers

Juan Manuel Fangio (Argentina | Alfa Romeo)

Nino Farina (Italy | Alfa Romeo)

Luigi Fagioli (Italy | Alfa Romeo)

Reg Parnell (UK | Alfa Romeo)

David Murray (UK | Maserati)

David Hampshire (UK | Maserati)

Leslie Johnson (UK | ERA)

Peter Walker (UK | ERA)

Joe Fry (UK | Maserati)

Cuth Harrison (UK | ERA)

Bob Gerard (UK | ERA)

Yves Giraud-Cabantous (France | Talbot-Lago)

Louis Rosier (France | Talbot-Lago)

Phillippe Étancelin (France | Talbot-Lago)

Eugène Martin (France | Talbot-Lago)

Johnny Claes (Belgium | Talbot-Lago)

Louis Chiron (Monaco | Maserati)

Toulo de Graffenreid (Switzerland | Maserati)

Prince Birabongse Bhanudej Bhanubandh (Thailand | Maserati)

Felice Bonetto (Italy | Maserati)

Joe Kelly (Ireland | Alta)

Geoffrey Crossley (UK | Alta)

The pre-race build-up

Practice took place on Thursday, May 11, with qualifying the subsequent day — and it was absolutely clear that Alfa Romeo were the favorites. At that time, Italian manufacturers were the strongest, with the most powerful cars and the most organized race teams. Without Ferrari, though, there wasn't expected to be much of a challenge.

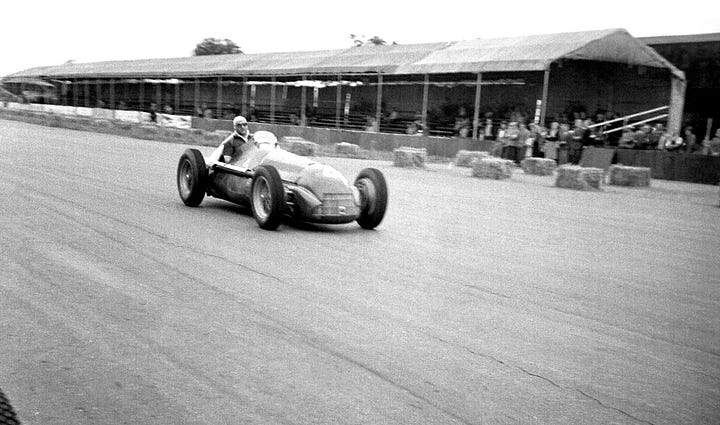

In 1950, Silverstone was a 2.889-mile track outlined with Daily Express-adorned hay bales, meaning would could expect a sub-two minute lap in qualifying — a session that took place throughout the day as opposed to the current “stages” of qualifying we currently see in F1.

Why Silverstone? What made that track an ideal F1 opener as opposed to something more prestigious, like Monaco?

Well, we have no idea! Britain's representative in the FIA/AIACR was a man named Earl Howe, who was also a chairman of the Royal Automobile Club Executive Committee, was also a former Grand Prix driver. He'd helped reintroduce international Grand Prix racing in the UK after World War II, and it's quite likely that he had plenty of clout with the higher-ups when it came time to organize the race.

Teams turned up with a variety of equipment — some with shiny, freshly painted, and professional-looking vans; others with their race cars hooked up to the back of a well-used trailer. They set up shop in the “paddock,” which at the time was basically just a wide-open dirt patch where teams were expected to conduct their pre-race preparation, and they scoped out some space on the pit wall to attend to their cars.

Our qualifying classification looked a little something like this:

Nino Farina - 1:50.8

Luigi Fagioli - 1:51.0

Juan Manuel Fangio - 1:51.2

Reg Parnell - 1:52.2

Prince Bira - 1:52.6

Yves Giraud-Cabantous - 1:53.4

Eugène Martin - 1:55.4

Toulo de Graffenreid - 1:55.8

Louis Rosier - 1:56.0

Peter Walker - 1:56.6

Louis Chiron - 1:56.6*

Leslie Johnson - 1:57.4

Bob Gerard - 1:57.4 *

Philippe Étancelin - 1:57.8

Cuth Harrison - 1:58.4

David Hampshire - 2:01.0

Geoffrey Crossley - 2:02.6

David Murray - 2:05.6

Joe Kelly - 2:06.2

Joe Fry - 2:07.0

Johnny Claes - 2:08.8

* Any ties in times between two competitors would be settled in favor of the driver who set their lap first.

At that time, the grid was set up in a 4-3-4-3 format, meaning that the first row was composed of the four fastest drivers, while the second row featured the following three, the third row four drivers, and so on.

The 1950 British Grand Prix: Race day!

A record-breaking crowd of 150,000 spectators turned up at an otherwise quiet airfield in England that Saturday afternoon for a 70-lap race set to create an exceptional legacy viewed by none other than members of the Royal Family.

Nino Farina launched into a decisive lead when the flag fell to signal the race start, with the Alfa Romeo crew lining up behind him as was anticipated.

Almost immediately, the lesser cars start retiring (sorry, ERA). Leslie Johnson smoked out with a failed compressor on the second lap and abandoned his car in the infield; not long after, Peter Walker retired. Walker had already relinquished his car to second driver Tony Rolt, but their gearbox problems are too substantial to fix, and they call it a day.

“Thus early the race is robbed of all real interest and we settle down to see a demonstration of Italian supremacy that is to cost £1,000 in prize money, apart from starting-fees,” Motor Sport Magazine wrote of the race.

Up at the front, with little competition to slow him down, Nino Farina was hitting speeds just above 90 mph, while behind him, his fellow Alfa drivers followed his path and more and more drivers abandoned their cars in the pits or along the side of the road. Oh, and poor Reg Parnell ran over a rabbit!

When it cam time to pit, the Alfa Romeo team was able to service its drivers in 30 seconds or less, with much of the rest of the field requiring 50 second or more — both due to inexperience and the fact that many needed spark plug changes.

At the 50-lap mark, Fangio — who had inherited the lead — lost it to Nino Farina. Even though he was able to carve back some of the gap, he nicked a straw bale at Stowe and was forced to retire.

Luigi Fagioli, too, had a go at Farina; in the final five laps, he carved the gap to the leader down from 41.8 seconds to 2.6 but ultimately ran out of time to make a pass.

The top three drivers celebrated on the podium, with the top five securing points. In sixth, Bob Gerard took home the Fred Craner Memorial Trophy, which was an award handed out to the best-placing British driver racing a British car.

In all the historic hubbub, we do tend to forget the fact that the logistics of this race were… a little bit of a mess. As Motor Sport Magazine wrote:

The R.A.C. G.P. de l’Europe, then, was no better than preceding races in the series, a sentiment with which we feel sure those who arrived late because of traffic congestion, those who spent four hours or so getting out of the car parks, those who received the wrong passes and those honorary club marshals who had to sleep the Friday night in old tents because R.A.C. patrols had taken the beds in the huts, will readily concur.

Big soirées and fancy dinners after Grand Prix events weren't common at the time, and Silverstone was out in the countryside, so the field of drivers retired to the beer tent after the race to swap stories about their inaugural Grand Prix experience.

1950 British Grand Prix finishing order

Nino Farina

Luigi Fagioli +2.6

Reg Parnell +52.0

Yves Giraud-Cabantous +2 laps

Louis Rosier +2 laps

Bob Gerard +3 laps

Cuth Harrison +3 laps

Philippe Ètancelin +5 laps

David Hampshire +6 laps

Joe Fry (shared with Brian Shawe-Taylor) +6 laps

Johnny Claes +6 laps

Retirements:

Juan Manuel Fangio - oil pipe, lap 62

Joe Kelly - not classified, lap 57

Prince Bira - out of fuel, lap 49

David Murray - engine trouble, lap 44

Geoffrey Crossley - transmission, lap 43

Toulo de Graffenreid - engine, lap 36

Louis Chiron - clutch, lap 24

Eugène Martin - oil pressure, lap 8

Peter Walker (shared with Tony Rolt) - gearbox, lap 5

Leslie Johnson - compressor, lap 2

More resources

The full race program for the 1950 British Grand Prix is available online, and you can skim it here.

Motor Sport has released colorized video highlights of the race!

Love this piece, Elizabeth. The Ferrari note is interesting. The only explanation I'd ever read about Ferrari missing Silverstone was that he thought his 125 F1 (or the engine, at least) wasn't ready. But it seems this has been a topic of debate over the years, and Enzo never set it straight.

Do you know why Felice Bonetto didnt start the race?